Bandwidth-wise, images are hogs. They are the largest average web site payload (62%), and they are most often the content bottleneck. When images arrive, they come tripping onto the page, pushing other elements around and triggering a clumsy repaint. They come “chop chop chop chop chop down†or you get nothing until suddenly “boom!†out of nowhere there it is. We all know what I’m talking about when I say “chop chop down†and “boom†and it makes us a little bit sick, because we sense how much time we’ve lost of our precious, short lives, waiting for pictures to download.

A missed opportunity

Photos are the main culprit when it comes to slow rendering. They are the most common type of image requested and on average weigh more. They are millions of colors and pixel depth is increasing. They are beautiful, and we don’t want to compromise on quality.

Web-optimized photos are jpegs, and jpegs come in two flavors: baseline and progressive. A baseline jpeg is a full-resolution top-to-bottom scan of the image, and a progressive jpeg is a series of scans of increasing quality. And that’s how they render; baseline jpegs paint top to bottom (“chop chop chop…”), and progressive jpegs quickly stake out their territory and refine (or at least that’s the idea).

Progressive jpegs are better because they are faster. Appearing faster is being faster, and perceived speed is more important that actual speed. Even if we are being greedy about what we are trying to deliver, progressive jpegs give us as much as possible as soon as possible. They assist us in our challenge of delivering big beautiful photos today.

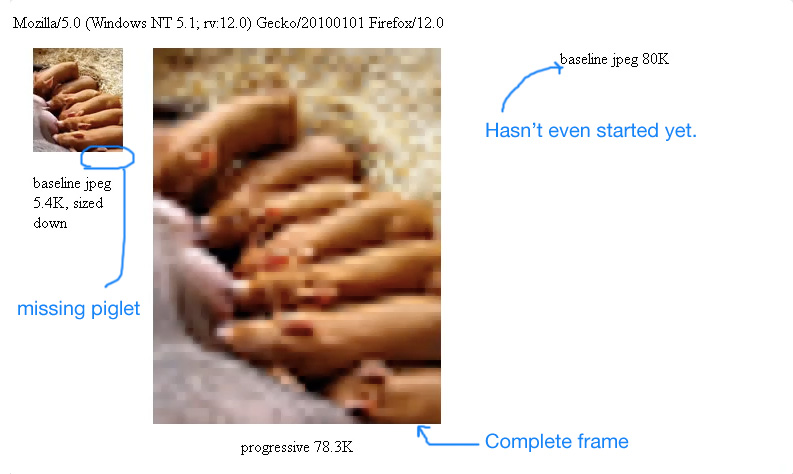

Experimenting locally with a throttled bandwidth, an 80K progressive jpeg beats a 5K baseline jpeg (the same image, downsized) to the page in Firefox on Windows. This should blow your mind. Sure, the progressive jpeg’s first pass is low-resolution, but it contains as much information, or more, as the small image. And if you are zoomed out, perhaps on a mobile device, you will not notice it’s low-res. That’s responsive images working for us right now!

Basically, progressive jpegs are better. So what’s the most common type of jpeg online? You guessed it: baseline, and by a very wide margin. In a thousand-image sample, 92.6% are baseline.

No worries, we just need to declare progressive jpegs a best practice and get the rest of the world on-board with us. But in order to declare progressive jpeg a best practice, we need to be confident that it is. And to do so we need to first understand what browser support for this type of jpeg looks like today.

Reality Check #1

Progressive jpegs are displayed in all browsers, that’s not a worry. Our concern is how they render.

Behavior of progressive jpegs across browsers

| Browser (specific version tested) | Foreground progressive jpeg renders | Background progressive jpeg renders |

|---|---|---|

| Chrome (v 25.0.1323.1 dev Mac, 23.0.1271.97 m Win) | progressively (superfast!) | progressively (superfast!) |

| Firefox (v 15.0.1 Mac, 12.0 Win) | progressively (superfast!) | instantly after file download (slow) |

| Internet Explorer 8 | instantly after file download (slow) | instantly after file download (slow) |

| Internet Explorer 9 | progressively (superfast!) | instantly after file download (slow) |

| Safari (v 6.0 Desktop, v 6.0 Mobile) | instantly after file download (slow) | instantly after file download (slow) |

| Opera (v 11.60) | instantly after file download (slow) | instantly after file download (slow) |

These are disappointing results, but overall, market share and progressive rendering for progressive jpegs are trending upward. Support is currently at about 65% (Chrome + Firefox + IE9).

Unfortunately, the browsers that do not render progressive jpegs progressively render them all at once after download is complete, which makes them less progressive and slower than baseline jpegs. While baseline rendering is not as immediate and smooth as progressive rendering, at least it’s something while we wait, and the “chop chop” is a kind of progress indicator (a good thing). We can’t underestimate the reassurance we give users when they see something is happening.

By choosing progressive jpegs we are giving a majority of users an excellent experience and a minority — but a significant minority — a worse experience. But if we select baseline jpegs because it is a less poor experience in a minority of views, that’s a terrible compromise. We need to offer the best experience to our users, and look ahead.

Reality Check #2

You might ask “Aren’t progressive jpegs bigger than regular jpegs? Don’t we pay for the ‘layers’?” This is true for other types of interlaced images, but not jpegs. A progressive jpeg is usually a few kilobytes smaller than its baseline version. Plotting the savings of 10000 random baseline jpegs converted to progressive, Stoyan Stefanov discovered a valuable rule of thumb: files that are over 10K will generally be smaller using the progressive option.

It would be an easier sell if we could say progressive jpegs are always smaller, so always make progressive jpegs. Stoyan helps us out here. He says “One observation about the 10K rule is that when baseline is smaller, it’s smaller by a small margin. When progressive is smaller it’s usually a lot smaller. So it’s ok to say go 100% progressive and you’ll do better.”

That’s exactly what I wanted to hear! For all the baseline jpegs we’ve been serving, we’ve been missing opportunities in file size and perceived speed. Choosing the progressive option is win-win, and should always be the default. Then, after all jpegs are progressive, if we want to optimize further, it’s just a few bytes we’ll save and only on our smallest images.

The reason baseline jpegs are most common online, no doubt, is because image-optimization tools make them by default. However, all of the ones I looked at — Photoshop, Fireworks, ImageMagick, jpegtran — have a progressive option. Therefore, to serve progressive jpegs you’ll need to consciously modify your image optimization process.

I’d expect Smushit to translate baseline jpegs to progressive, and sure enough it does. (Smushit, btw, can be run from the command line and integrated into your image optimization process.)

How do you know if your jpegs are progressive? Here are a few ways to identify jpeg type:

- ImageMagick — On the command line run: identify -verbose mystery.jpg | grep Interlace The output will either be “Interlace: JPEG” or “Interlace: None.”

- Photoshop — Open file. Select File -> Save for Web & Devices. If it’s a progressive jpeg, the Progressive checkbox will be selected.

- Any browser — Baselines jpegs will load top to bottom, and progressive jpegs will do something else. If the file loads too fast you may need to add bandwidth throttling. I use ipfw on my Mac.

Reality Check #3

According to this progressive jpeg FAQ, each progressive scan requires about the same amount of CPU as the entire baseline jpeg would take to render. This is not a concern for desktops but possibly for mobile devices.

The extra computation is a disadvantage but not a deal breaker. Delivering photos on small hardware is a challenge regardless. I know this because I’m writing a photo gallery application with infinite scrolling and it crashes on iPad. If you are handling a lot of images, you will have challenges on mobile anyway — different challenges.

As we’ve seen in the chart, Mobile Safari does not render progressive jpegs progressively anyway, and probably because they tax the CPU. But this is not a new image file format. Therefore, it wasn’t an option for browsers, even mobile browsers, to choose not to support progressive jpegs. Hopefully soon mobile browsers will leverage progressive rendering, but it makes sense why they currently don’t. It’s also a crying shame; we could really use the speed and file size savings progressive jpegs give us for mobile. When I said they are a kind of solution for responsive images right now, well, they would be, but aren’t yet.

Onward

In the last few days, Google got on-board with their Mod_Pagespeed service, making convert_jpeg_to_progressive a core filter. SPDY does as well, translating jpegs that are over 10K to progressive by default, following Stoyan’s rule of thumb. This will make browsers that support incremental display seem much faster. As you can see in the chart above that includes Google Chrome, so it makes sense that Google would make this choice. I’m not going to say that because “do-no-evil-make-the-web-faster” Google has selected progressive jpeg to be a best practice so should we. But it’s more data and validation. Most importantly, it shows that progressive jpeg — a format that has been in a kind of deep freeze for a decade — has staged a comeback.

And even though not all current browsers make use of progressive jpeg’s progressive rendering, the ones that do really benefit, and we get file size savings across the board. It’s our best option today and we should use it. Progressive jpegs are the future, not the past.