Yoav Weiss (@yoav, @yoavweiss) has been working on mobile web performance for longer than he cares to admit, on the server side as well as in browsers.

He now works at Shopify, bringing the web platform to where online commerce needs it to be. He also co-chairs the Web Performance Working Group and the Web Incubator Community Group at the W3C, to make sure the web is as fast as it can be, and full of new ideas.

Yoav takes image bloat on the web as a personal insult, which is why he joined the Responsive Images Community Group and implemented the various responsive images features in Blink and WebKit. That was his gateway drug into the wonderfully complex world of browsers and standards.

When he's not writing code, he' probably wandering the Alps, mowing the lawn, or playing board games with his family.

Loading styles on the web is something that looks trivial at first.

You just add a <link rel=stylesheet> to your page (or <style> for inline styles) and you’re done.

But if you wanted to load CSS fast, all of the sudden you run into trouble…

Assuming you have a traditional web app (or what the kids call Multi-Page App/MPA), you now need to make tradeoffs:

- You most probably want the CSS that’s critical to the page the user is loading to block the rendering of that page, to avoid FOUC.

- At the same time, you don’t want to load all the styles any page on your site may need, as that would delay that critical first load (and your FCP and LCP metrics on that page).

- But, if you were to only load the critical CSS on every page on your site, you’re likely loading way too many overlapping styles, as different pages on your site likely shared a ton of styles amongst themselves.

The above tradeoffs naturally break down into two options:

- Either embed critical inline styles for every page, or create an external style that represents that critical style for every specific page.

- Full CSS, loaded up front.

Neither of these options is ideal, as we outlined above: you either waste time on the extremely important landing page load, or you waste time on every follow-up navigation.

With full CSS there’s also extra, hidden cost – if we’re loading unused CSS rules, the browser is potentially spending more time in style calculations figuring out that these rules aren’t actually used.

Compression dictionaries give us a third option, that avoids these tradeoffs altogether!

How??

Compression dictionaries have two different modes: using an existing resource as a dictionary, as well as downloading an out-of-band, separate dictionary. The former is a “delta compression” method, where one resource is used to compress future resources. The latter enables us to set site-wide “shared” dictionaries that are then used to compress many different resources.

For CSS loading, we can use these two different modes in a complementary way.

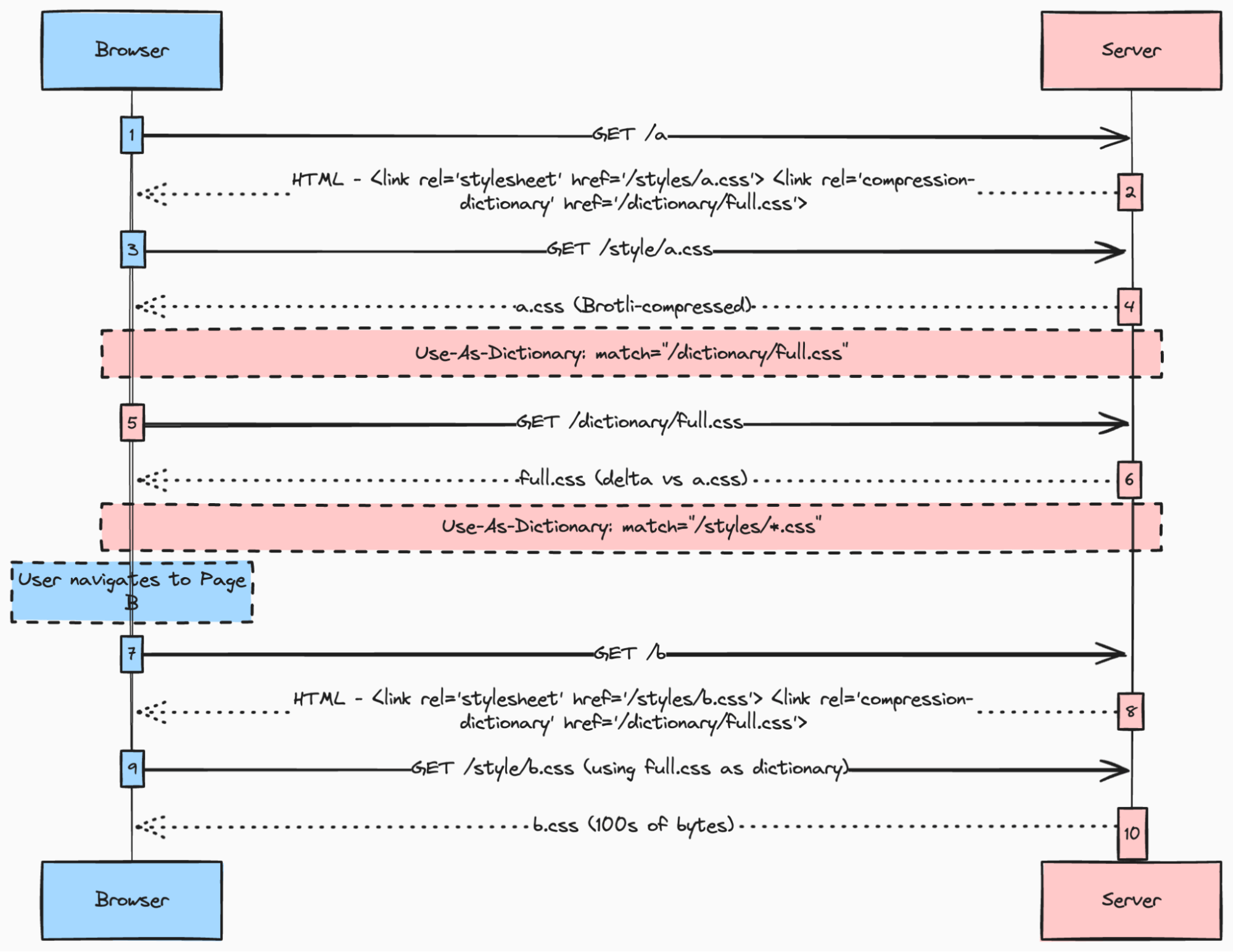

Looking at an example, let’s say that our site is composed of pages A and B, and a user lands on page A. Our URL structure would be something like:

https://example.com/awhich loadshttps://example.com/style/a.csshttps://example.com/bwhich loadshttps://example.com/style/b.css

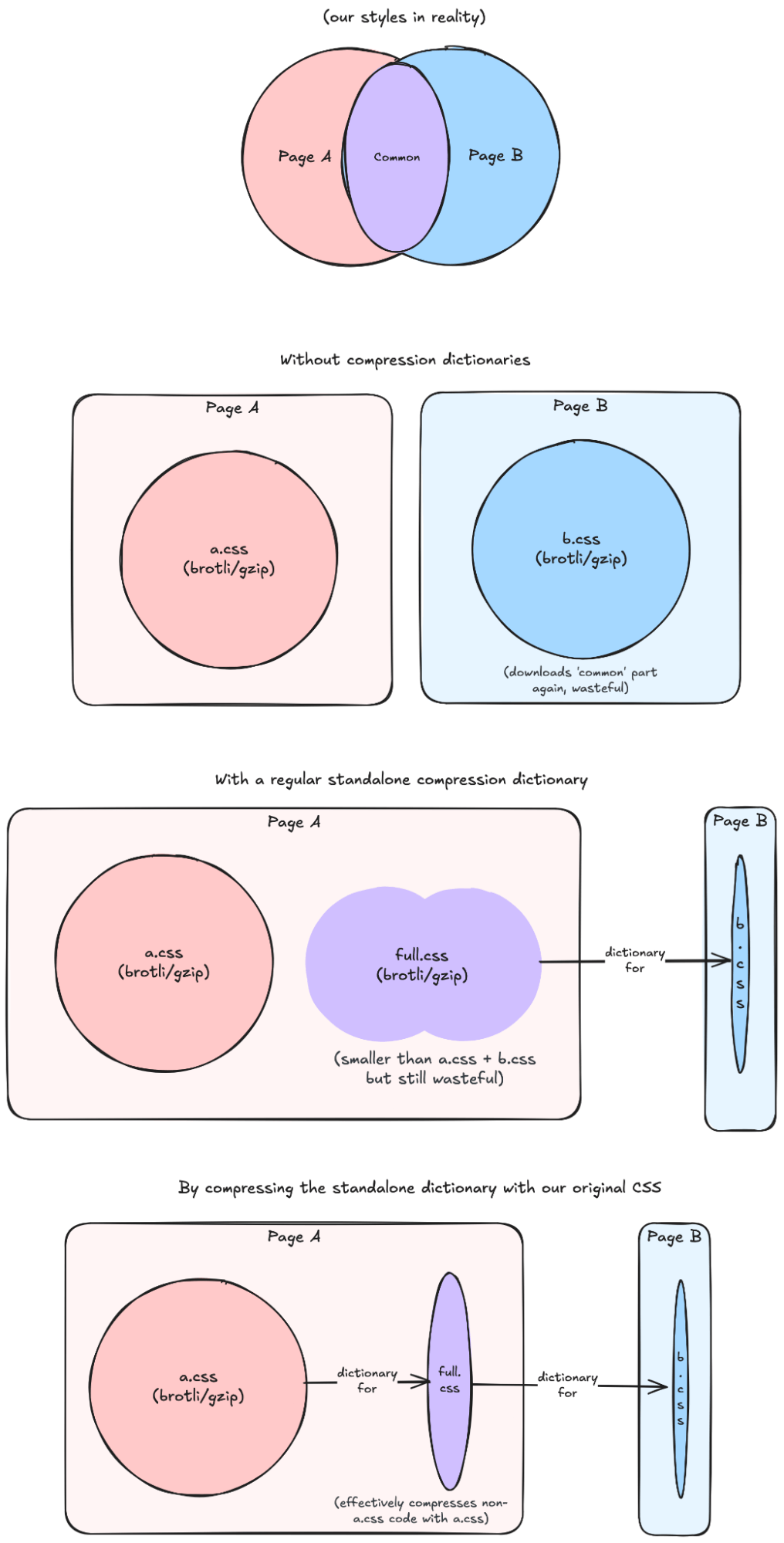

a.css and b.css would tend to have a lot of overlap, and so the loading of the follow-up page would be slower than it should be.

But we can use compression dictionaries to enhance that flow and reduce overhead.

We can create a larger https://example.com/dictionary/full.css, that would be a superset of both CSS files. full.css will never be used as an actual stylesheet, its sole purpose is as a compression dictionary for other stylesheets.

Then, when serving a stylesheet from the /style/ directory, we can add a Use-As-Dictionary: match="/dictionary/full.css" header.

We can similarly add a <link rel="compression-dictionary" href="/dictionary/full.css"> tag to our various pages.

And finally we can serve /dictionary/full.css with a Use-As-Dictionary: match="/styles/*.css" header.

What does that do??

When doing the above:

- Page A loads

a.csswith regular Brotli compression. Then at idle time, it discovers the<link rel="compression-dictionary">tag and loadsfull.css, but it loads it while usinga.cssas its dictionary (because of theUse-As-Dictionary: match="/dictionary/full.css"HTTP headers). That means that we only pay the loading cost of the rules offull.cssthat aren’t already present ina.css- Note: Compressing the full CSS using the landing page CSS (

a.css) as a dictionary adds some complexity, as we’d need to pre-compressfull.csswith all the potential landing pages as dictionaries. The main benefit of doing that is bandwidth savings, rather than time savings. So while the complexity cost seems worthwhile at scale, this is a part you can probably skip without significant user-facing consequences, other than some wasted bandwidth.

- Note: Compressing the full CSS using the landing page CSS (

- Then when the user navigates to page B,

b.cssis loaded withfull.css(which is its superset) as its dictionary. That means that over the network, we only load a few hundred bytes.

If you prefer to see this live, you can check out the demo.

While the demo is composed of small pages with relatively minor CSS files, real life sites can have 100s of KBs of CSS, where the benefits would be visible.

Benefits

For the initial landing page, this method is similar to the critical CSS one – the page only has to download and process the CSS it actually needs.

After the initial loading, the page loads (at idle time) the delta between the full CSS for the site, and the landing page CSS.

Then on followup navigations, the download cost of CSS is close to zero in terms of bandwidth. In terms of runtime processing, these pages also only process the CSS they actually use.

To visualise:

What happens when content updates?

When the CSS for the site updates, repeat visitors will see a slightly different, but still optimized flow.

The CSS for the landing page will be dictionary-compressed using the older full CSS, which is a superset of its past version. That means we’d effectively only download the code changes in the new version.

The new full CSS would then download using the (new) landing page CSS, similar to the regular flow.

Server-side considerations

Because this method relies on delivering deltas from the various pages’ critical CSS and a full CSS dictionary, the number of resource variants we’d need to send is linear to the number of pages, and can be generated statically.

For a site with N different page types, we’d need to calculate N critical CSS files (in case these pages are the landing pages), N deltas between them and the full CSS (to deliver the full CSS dictionary) and N representations of the critical CSS using the full CSS dictionary (for followup pages).

We would need some server side logic to handle varying the delivery of these different variants based on the Dictionary-ID or Available-Dictionary header.

Supporting the “content update” scenario would require a bit more server side logic, as it requires compressing the current CSS using older code versions. That would require either on-the-fly compression, or static generation of X past versions for all N potential landing page types. So that scenario can get a bit more complex to support in a static setting.

From a caching perspective, you’ll need to make sure that your CDN cache is varied on Available-Dictionary or Dictionary-Id. You can do that by having a CDN-specific Vary header, or by changing the cache key your CDN considers in its configuration. Having these different variants can reduce your effective CDN cache hit ratios and somewhat increase your server’s load.

What about non-Chromium browsers?

The above method falls back gracefully to “critical CSS” in browsers that don’t yet support compression dictionaries. At the same time, compression dictionaries are being worked on in Firefox (and maybe also Safari). Once these browsers get support, this will Just Work™.

To sum it up

I think compression dictionaries can revolutionize the way we’re serving CSS to users, and can significantly reduce its costs. The technology is already here for you to use in Chromium, and is likely to make it to other browsers in the near future. And while it will require some server-side logic, most of the heavy lifting can be done as static generation.

Credits: this CSS delivery method was developed during discussions with Ryan Townsend, building on Pat Meenan‘s work with compression dictionaries.

Also, huge thanks to Ryan for reviewing this post, providing input and creating the Venn diagram illustration(!!), as well as to Mateusz Krzeszowiak for his review and input to this post.