Stoyan (@stoyanstefanov) is a frontend engineer, writer ("JavaScript Patterns", "Object-Oriented JavaScript"), speaker (JSConf, Velocity, Fronteers), toolmaker (Smush.it, YSlow 2.0) and a guitar hero wannabe.

Nice 5 “R” words in the title, eh? Let’s talk about rendering – a phase that comes in the Life of Page 2.0 after, and sometimes during, the waterfall of downloading components.

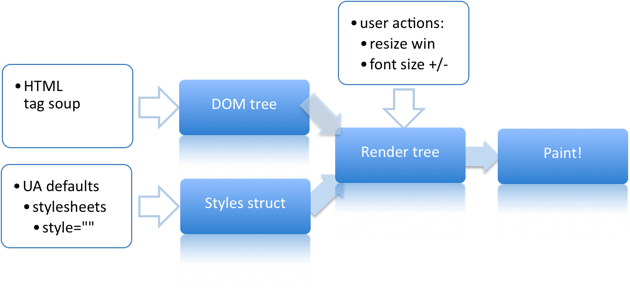

So how does the browser go about displaying your page on the screen, given a chunk of HTML, CSS and possibly JavaScript.

The rendering process

Different browsers work differently, but the following diagram gives a general idea of what happens, more or less consistently across browsers, once they’ve downloaded the code for your page.

- The browser parses out the HTML source code (tag soup) and constructs a DOM tree – a data representation where every HTML tag has a corresponding node in the tree and the text chunks between tags get a text node representation too. The root node in the DOM tree is the

documentElement(the<html>tag) - The browser parses the CSS code, makes sense of it given the bunch of hacks that could be there and the number of

-moz,-webkitand other extensions it doesn’t understand and will bravely ignore. The styling information cascades: the basic rules are in the User Agent stylesheets (the browser defaults), then there could be user stylesheets, author (as in author of the page) stylesheets – external, imported, inline, and finally styles that are coded into thestyleattributes of the HTML tags - Then comes the interesting part – constructing a render tree. The render tree is sort of like the DOM tree, but doesn’t match it exactly. The render tree knows about styles, so if you’re hiding a

divwithdisplay: none, it won’t be represented in the render tree. Same for the other invisible elements, likeheadand everything in it. On the other hand, there might be DOM elements that are represented with more than one node in the render tree – like text nodes for example where every line in a<p>needs a render node. A node in the render tree is called a frame, or a box (as in a CSS box, according to the box model). Each of these nodes has the CSS box properties – width, height, border, margin, etc - Once the render tree is constructed, the browser can paint (draw) the render tree nodes on the screen

The forest and the trees

Let’s take an example.

HTML source:

<html> <head> <title>Beautiful page</title> </head> <body> <p> Once upon a time there was a looong paragraph... </p> <div style="display: none"> Secret message </div> <div><img src="..." /></div> ... </body> </html>

The DOM tree that represents this HTML document basically has one node for each tag and one text node for each piece of text between nodes (for simplicity let’s ignore the fact that whitespace is text nodes too) :

documentElement (html)

head

title

body

p

[text node]

div

[text node]

div

img

...

The render tree would be the visual part of the DOM tree. It is missing some stuff – the head and the hidden div, but it has additional nodes (aka frames, aka boxes) for the lines of text.

root (RenderView)

body

p

line 1

line 2

line 3

...

div

img

...

The root node of the render tree is the frame (the box) that contains all other elements. You can think of it as being the inner part of the browser window, as this is the restricted area where the page could spread. Technically WebKit calls the root node RenderView and it corresponds to the CSS initial containing block, which is basically the viewport rectangle from the top of the page (0, 0) to (window.innerWidth, window.innerHeight)

Figuring out what and how exactly to display on the screen involves a recursive walk down (a flow) through the render tree.

Repaints and reflows

There’s always at least one initial page layout together with a paint (unless, of course you prefer your pages blank :)). After that, changing the input information which was used to construct the render tree may result in one or both of these:

- parts of the render tree (or the whole tree) will need to be revalidated and the node dimensions recalculated. This is called a reflow, or layout, or layouting. (or “relayout” which I made up so I have more “R”s in the title, sorry, my bad). Note that there’s at least one reflow – the initial layout of the page

- parts of the screen will need to be updated, either because of changes in geometric properties of a node or because of stylistic change, such as changing the background color. This screen update is called a repaint, or a redraw.

Repaints and reflows can be expensive, they can hurt the user experience, and make the UI appear sluggish.

What triggers a reflow or a repaint

Anything that changes input information used to construct the rendering tree can cause a repaint or a reflow, for example:

- Adding, removing, updating DOM nodes

- Hiding a DOM node with

display: none(reflow and repaint) orvisibility: hidden(repaint only, because no geometry changes) - Moving, animating a DOM node on the page

- Adding a stylesheet, tweaking style properties

- User action such as resizing the window, changing the font size, or (oh, OMG, no!) scrolling

Let’s see a few examples:

var bstyle = document.body.style; // cache bstyle.padding = "20px"; // reflow, repaint bstyle.border = "10px solid red"; // another reflow and a repaint bstyle.color = "blue"; // repaint only, no dimensions changed bstyle.backgroundColor = "#fad"; // repaint bstyle.fontSize = "2em"; // reflow, repaint // new DOM element - reflow, repaint document.body.appendChild(document.createTextNode('dude!'));

Some reflows may be more expensive than others. Think of the render tree – if you fiddle with a node way down the tree that is a direct descendant of the body, then you’re probably not invalidating a lot of other nodes. But what about when you animate and expand a div at the top of the page which then pushes down the rest of the page – that sounds expensive.

Browsers are smart

Since the reflows and repaints associated with render tree changes are expensive, the browsers aim at reducing the negative effects. One strategy is to simply not do the work. Or not right now, at least. The browser will setup a queue of the changes your scripts require and perform them in batches. This way several changes that each require a reflow will be combined and only one reflow will be computed. Browsers can add to the queued changes and then flush the queue once a certain amount of time passes or a certain number of changes is reached.

But sometimes the script may prevent the browser from optimizing the reflows, and cause it to flush the queue and perform all batched changes. This happens when you request style information, such as

offsetTop,offsetLeft,offsetWidth,offsetHeightscrollTop/Left/Width/HeightclientTop/Left/Width/HeightgetComputedStyle(), orcurrentStylein IE

All of these above are essentially requesting style information about a node, and any time you do it, the browser has to give you the most up-to-date value. In order to do so, it needs to apply all scheduled changes, flush the queue, bite the bullet and do the reflow.

For example, it’s a bad idea to set and get styles in a quick succession (in a loop), like:

// no-no! el.style.left = el.offsetLeft + 10 + "px";

Minimizing repaints and reflows

The strategy to reduce the negative effects of reflows/repaints on the user experience is to simply have fewer reflows and repaints and fewer requests for style information, so the browser can optimize reflows. How to go about that?

- Don’t change individual styles, one by one. Best for sanity and maintainability is to change the class names not the styles. But that assumes static styles. If the styles are dynamic, edit the

cssTextproperty as opposed to touching the element and its style property for every little change.// bad var left = 10, top = 10; el.style.left = left + "px"; el.style.top = top + "px"; // better el.className += " theclassname"; // or when top and left are calculated dynamically... // better el.style.cssText += "; left: " + left + "px; top: " + top + "px;";

- Batch DOM changes and perform them “offline”. Offline means not in the live DOM tree. You can:

- use a

documentFragmentto hold temp changes, - clone the node you’re about to update, work on the copy, then swap the original with the updated clone

- hide the element with

display: none(1 reflow, repaint), add 100 changes, restore the display (another reflow, repaint). This way you trade 2 reflows for potentially a hundred

- use a

- Don’t ask for computed styles excessively. If you need to work with a computed value, take it once, cache to a local var and work with the local copy. Revisiting the no-no example from above:

// no-no! for(big; loop; here) { el.style.left = el.offsetLeft + 10 + "px"; el.style.top = el.offsetTop + 10 + "px"; } // better var left = el.offsetLeft, top = el.offsetTop esty = el.style; for(big; loop; here) { left += 10; top += 10; esty.left = left + "px"; esty.top = top + "px"; }

- In general, think about the render tree and how much of it will need revalidation after your change. For example using absolute positioning makes that element a child of the body in the render tree, so it won’t affect too many other nodes when you animate it for example. Some of the other nodes may be in the area that needs repainting when you place your element on top of them, but they will not require reflow.

Tools

Only about a year ago, there was nothing that can provide any visibility into what’s going on in the browser in terms of painting and rendering (not that I am aware of, it’s of course absolutely possible that MS had a wicked dev tool no one knew about, buried somewhere in MSDN :P). Now things are different and this is very, very cool.

First, MozAfterPaint event landed in Firefox nightlies, so things like this extension by Kyle Scholz showed up. mozAfterPaint is cool, but only tells you about repaints.

DynaTrace Ajax and most recently Google’s SpeedTracer (notice two “trace”s :)) are just excellent tools for digging into reflows and repaints – the first is for IE, the second for WebKit.

Some time last year Douglas Crockford mentioned that we’re probably doing some really stupid things in CSS we don’t know about. And I can definitely relate to that. I was involved in a project for a bit where increasing the browser font size (in IE6) was causing the CPU go up to 100% and stay like this for 10-15 minutes before finally repainting the page.

Well, the tools are now here, we don’t have excuses any more for doing silly things in CSS.

Except, maybe, speaking of tools…, wouldn’t it be cool if the Firebug-like tools showed the render tree in addition to the DOM tree?

A final example

Let’s just take a quick look at the tools and demonstrate the difference between restyle (render tree change that doesn’t affect the geometry) and reflow (which affects the layout), together with a repaint.

Let’s compare two ways of doing the same thing. First, we change some styles (not touching layout) and after every change, we check for a style property, totally unrelated to the one just changed.

bodystyle.color = 'red'; tmp = computed.backgroundColor; bodystyle.color = 'white'; tmp = computed.backgroundImage; bodystyle.color = 'green'; tmp = computed.backgroundAttachment;

Then the same thing, but we’re touching style properties for information only after all the changes:

bodystyle.color = 'yellow'; bodystyle.color = 'pink'; bodystyle.color = 'blue'; tmp = computed.backgroundColor; tmp = computed.backgroundImage; tmp = computed.backgroundAttachment;

In both cases, these are the definitions of the variables used:

var bodystyle = document.body.style; var computed; if (document.body.currentStyle) { computed = document.body.currentStyle; } else { computed = document.defaultView.getComputedStyle(document.body, ''); }

Now, the two example style changes will be executed on click on the document. The test page is actually here – restyle.html (click “dude”). Let’s call this restyle test.

The second test is just like the first, but this time we’ll also change layout information:

// touch styles every time bodystyle.color = 'red'; bodystyle.padding = '1px'; tmp = computed.backgroundColor; bodystyle.color = 'white'; bodystyle.padding = '2px'; tmp = computed.backgroundImage; bodystyle.color = 'green'; bodystyle.padding = '3px'; tmp = computed.backgroundAttachment; // touch at the end bodystyle.color = 'yellow'; bodystyle.padding = '4px'; bodystyle.color = 'pink'; bodystyle.padding = '5px'; bodystyle.color = 'blue'; bodystyle.padding = '6px'; tmp = computed.backgroundColor; tmp = computed.backgroundImage; tmp = computed.backgroundAttachment;

This test changes the layout so let’s called it “relayout test”, the source is here.

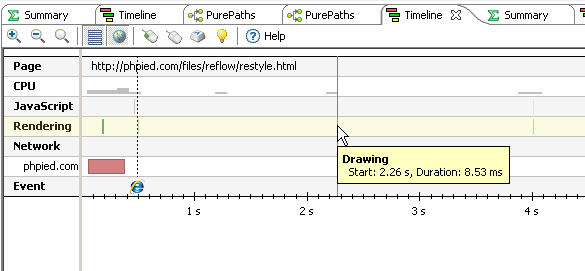

Here’s what type of visualization you get in DynaTrace for the restyle test.

Basically the page loaded, then I clicked once to execute the first scenario (requests for style info every time, at about 2sec), then clicked again to execute the second scenario (requests for styles delayed till the end, at about 4sec)

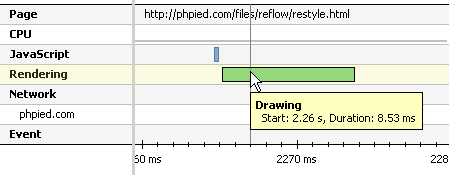

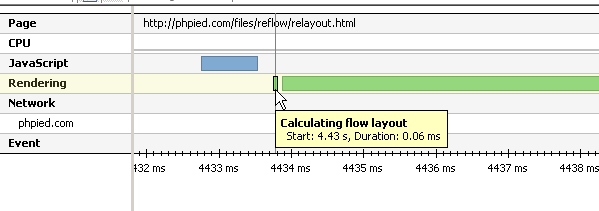

The tool shows how the page loaded and the IE logo shows onload. Then the mouse cursor is over the rendering activity following the click. Zooming into the interesting area (how cool is that!) there’s a more detailed view:

You can clearly see the blue bar of JavaScript activity and the following green bar of rendering activity. Now, this is a simple example, but still notice the length of the bars – how much more time is spent rendering than executing JavaScript. Often in Ajax/Rich apps, JavaScript is not the bottleneck, it’s the DOM access and manipulation and the rendering part.

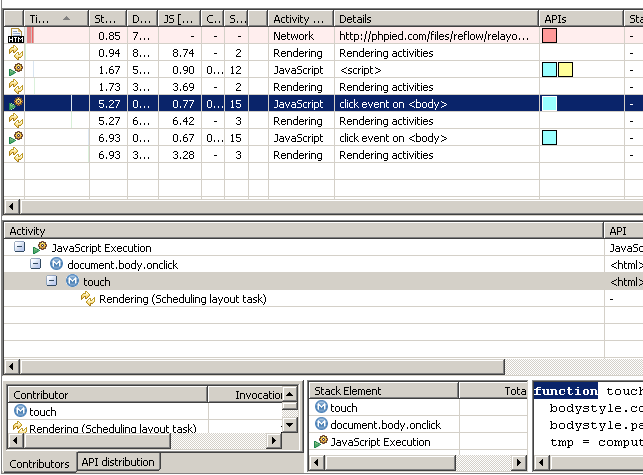

OK, now running the “relayout test”, the one that changes the geometry of the body. This time check out this “PurePaths” view. It’s a timeline plus more information about each item in the timeline. I’ve highlighted the first click, which is a JavaScript activity producing a scheduled layout task.

Again, zooming into the interesting part, you can see how now in addition to the “drawing” bar, there’s a new one before that – the “calculating flow layout”, because in this test we had a reflow in addition to the repaint.

Now let’s test the same page in Chrome and look at the SpeedTracer results.

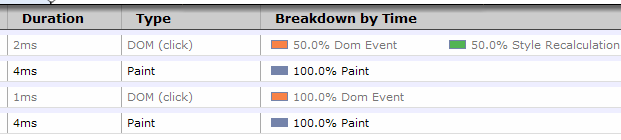

This is the first “restyle” test zoomed into the interesting part (heck, I think I can definitely get cused to all that zooming :)) and this is an overview of what happened.

Overall there’s a click and there’s a paint. But in the first click, there’s also 50% time spent recalculating styles. Why is that? Well, this is because we asked for style information with every change.

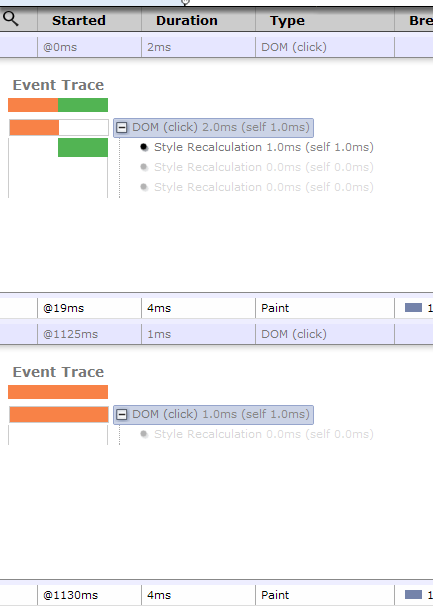

Expanding the events and showing hidden lines (the gray lines were hidden by Speedtracer because they are not slow) we can see exactly what happened – after the first click, styles were calculated three times. After the second – only once.

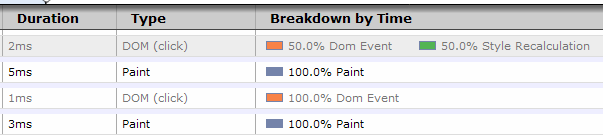

Now let’s run the “relayout test”. The overall list of events looks the same:

But the detailed view shows how the first click caused three reflows (because it asked for computed style info) and the second click caused only one reflow. This is just excellent visibility into what’s going on.

A few minor differences in the tools – SpeedTracer didn’t show when the layout task was scheduled and added to the queue, DynaTrace did. And then DynaTrace didn’t show the details of the difference between “restyle” and “reflow/layout”, like SpeedTracer did. Maybe simply IE doesn’t make a difference between the two? DynaTrace also didn’t show three reflows instead of one in the different change-end-touch vs. change-then-touch tests, maybe that’s how IE works?

Running these simple examples hundreds of times also confirms that for IE it doesn’t matter if you request style information as you change it.

Here’s some more data points after running the tests with enough repetitions:

- In Chrome not touching computed styles while modifying styles is 2.5 times faster when you change styles (restyle test) and 4.42 times faster when you change styles and layout (relayout test)

- In Firefox – 1.87 times faster to refrain from asking computed styles in restyle test and 1.64 times faster in the relayout test

- In IE6 and IE8, it doesn’t matter

Across all browsers though changing styles only takes half the time it takes to change styles and layout. (Now that I wrote it, I should’ve compared changing styles only vs. changing layout only). Except in IE6 where changing layout is 4 times more expensive then changing only styles.

Parting words

Thanks very much for working through this long post. Have fun with the tracers and watch out for those reflows! In summary, let me go over the different terminology once again.

- render tree – the visual part of the DOM tree

- nodes in the render tree are called frames or boxes

- recalculating parts of the render tree is called reflow (in Mozilla), and called layout in every other browser, it seems

- Updating the screen with the results of the recalculated render tree is called repaint, or redraw (in IE/DynaTrace)

- SpeedTracer introduces the notion of “style recalculation” (styles without geometry changes) vs. “layout”

And some more reading if you find this topic fascinating. Note that these reads, especially the first three, are more in depth, closer to the browser, as opposed to closer to the developer which I tried to do here.

- Mozilla: notes on reflow

- David Baron of Mozilla: Google tech talk on Layout Engine Internals for Web Developers

- WebKit: rendering basics – 6-part series of posts

- Opera: repaints and reflows is a part of an article on efficient JavaScript

- Dynatrace: IE rendering behavior