tl;dr: Progressive images render faster on HTTP2, thus increasing perceived performance. Take control of progressive JPEG’s scan layers to show meaningful image content with only 25% of image data sent. Use HTTP2 Server Push for progressive JPEG scan layers to maximize rendering performance for key images.

We Have An Image Problem

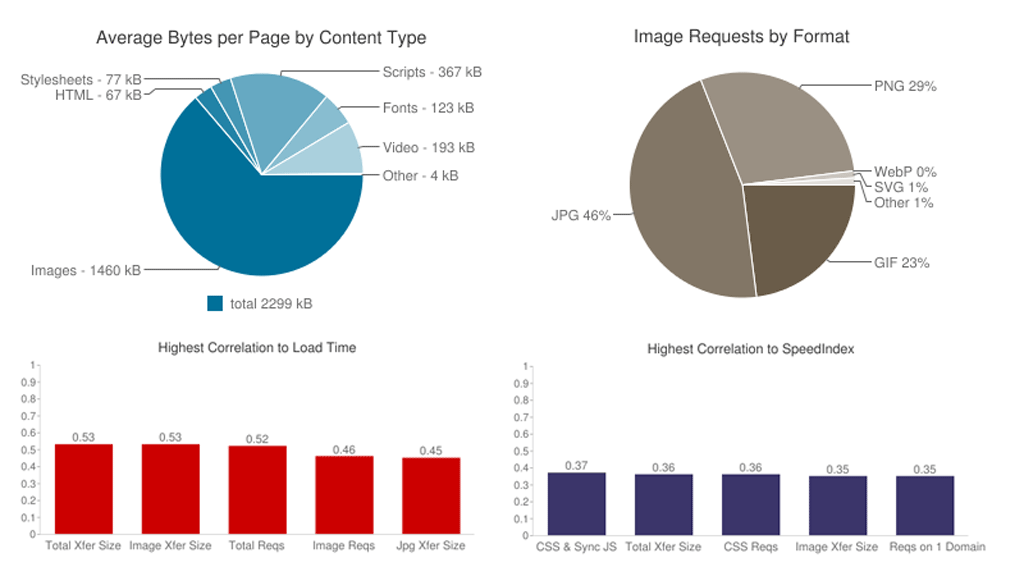

Images make the world go round: they engage, enrage & encourage us. The web as we know it depends on images. This comes at a price: images make up ~65% of average total bytes per page and have a high correlation to page load time as well as the Speed Index. They also grow by ~200kb year after year. In short, images are heavy and make things slow.

Images make the world go round: they engage, enrage & encourage us. The web as we know it depends on images. This comes at a price: images make up ~65% of average total bytes per page and have a high correlation to page load time as well as the Speed Index. They also grow by ~200kb year after year. In short, images are heavy and make things slow.

Get Compressin’!

The best way to counter negative effects of loading image assets is image compression: using tools such as Kornel Lesiński‘s ImageOptim, which utilizes great libraries like mozjpeg and pngquant, we can reduce image byte size without sacrificing visual quality. And thanks to libraries such as DSSIM we can ensure good visual quality testing different compression levels.

The best way to counter negative effects of loading image assets is image compression: using tools such as Kornel Lesiński‘s ImageOptim, which utilizes great libraries like mozjpeg and pngquant, we can reduce image byte size without sacrificing visual quality. And thanks to libraries such as DSSIM we can ensure good visual quality testing different compression levels.

The bad news is that even after reducing image byte size by an average ~29% per image using above tools and even making use of other image formats such as WebP, images are still likely to be the single largest asset type on any given website – closely followed by JavaScript. We need a way to deliver these crucial components for emotional engagement faster.

Enter Multiplexing

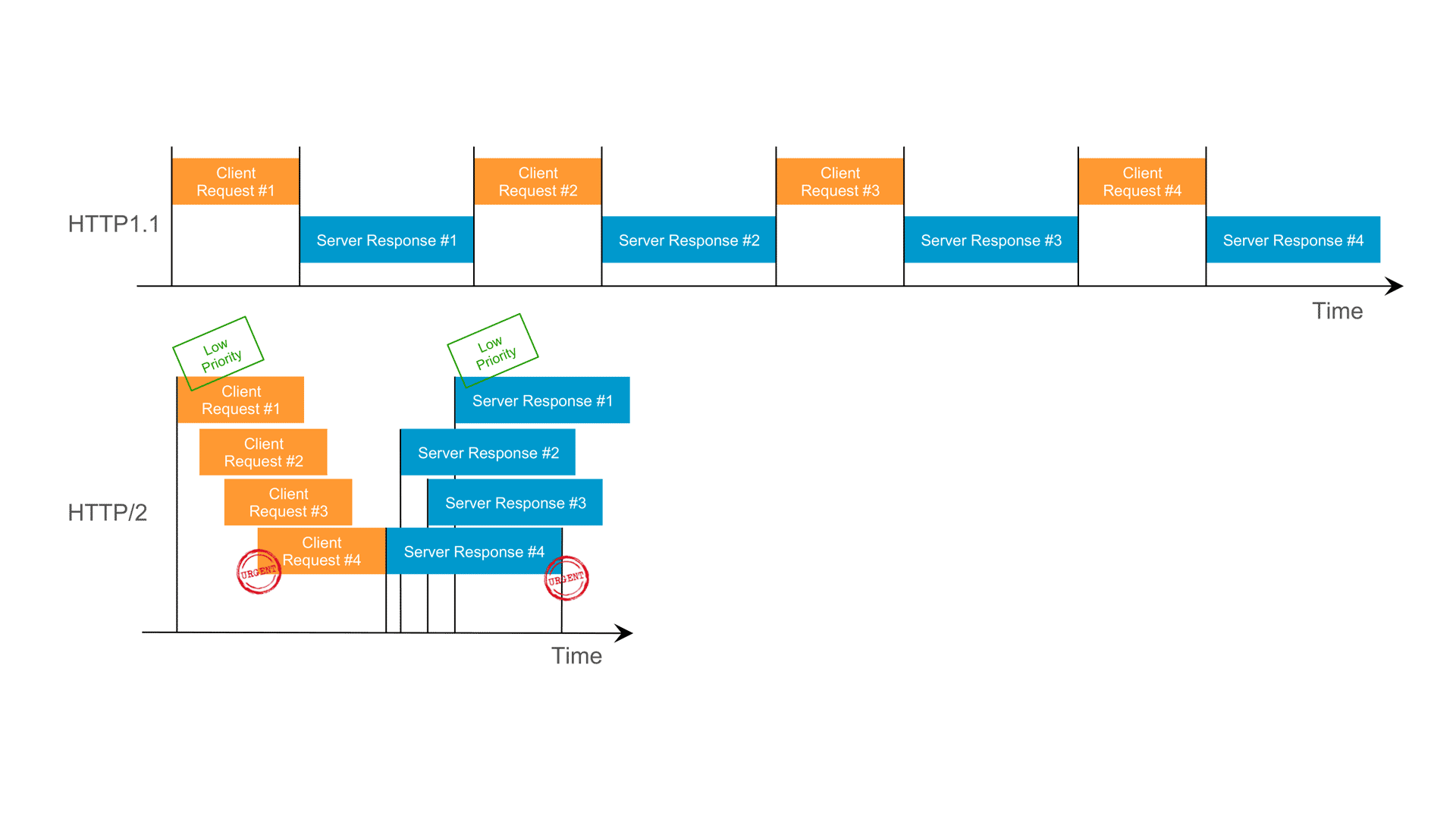

Part of the solution comes from a popular area of the performance conundrum: HTTP2. One of its main benefits is “Multiplexing”: the ability to handle multiple requests and responses at the same time, all using the same TCP connection.

Part of the solution comes from a popular area of the performance conundrum: HTTP2. One of its main benefits is “Multiplexing”: the ability to handle multiple requests and responses at the same time, all using the same TCP connection.

With Multiplexing, website assets load faster. Depending on site architecture, you can also prioritize resources inside a multiplexed connection: flagging assets such as critical CSS with high priority in HTTP2 will make them load sooner. On top of this, pushing not yet requested but crucial assets via HTTP2 Server Push can create a super fast perceived performance, when applied correctly. More on this later.

Multiplexing has a curious side-effect when it comes to image loading: certain kinds of images load significantly faster in terms of perceived performance because initial image information can be downloaded in parallel via HTTP2 Multiplexing. Progressive JPEGs and interlaced PNGs benefit from this.

Multiplexing has a curious side-effect when it comes to image loading: certain kinds of images load significantly faster in terms of perceived performance because initial image information can be downloaded in parallel via HTTP2 Multiplexing. Progressive JPEGs and interlaced PNGs benefit from this.

Progressive All The Things

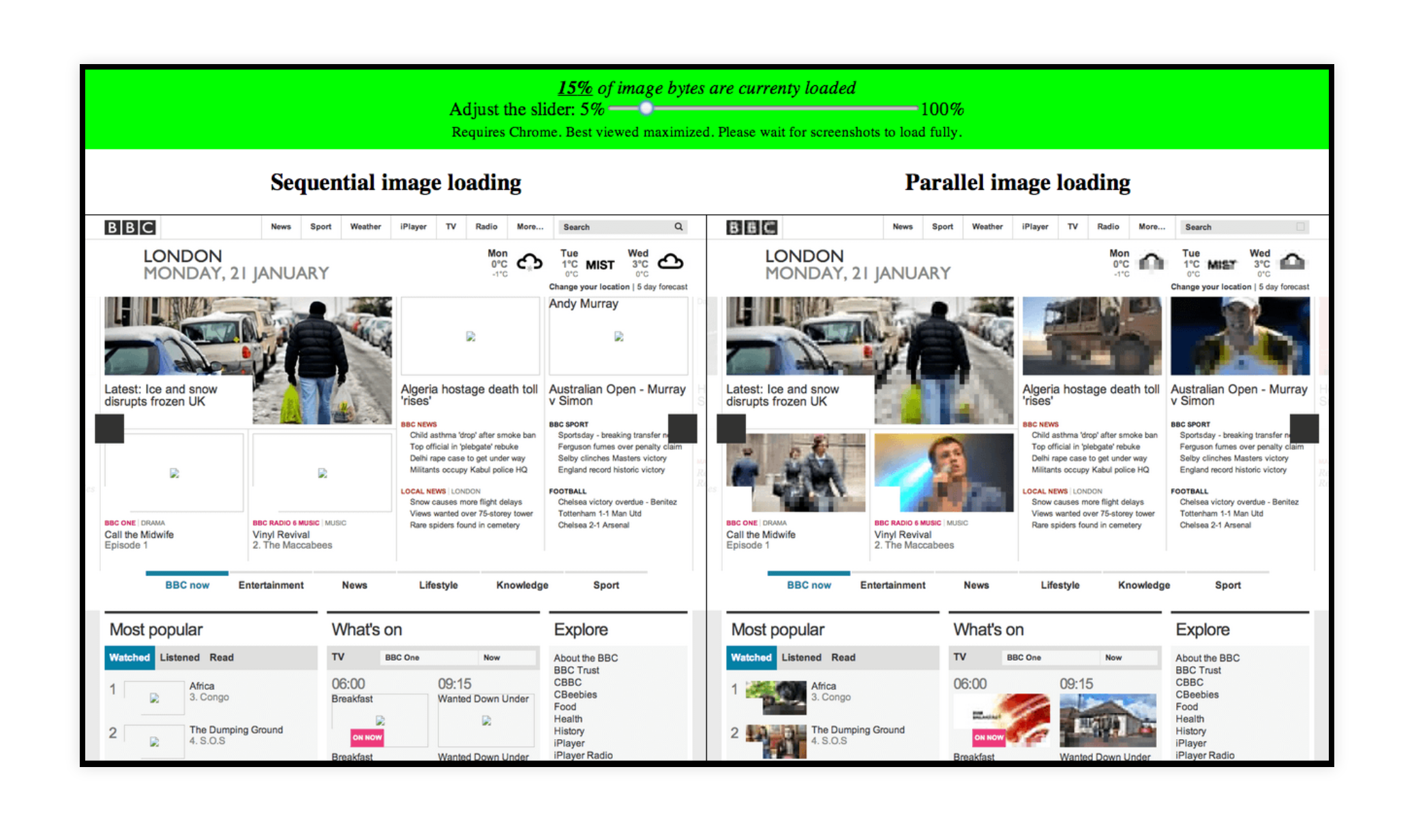

Progressive and interlaced images are like layer cake: they contain information not in a single stream that renders images from top left to bottom right, but as a stack of layers, each improving on information already shipped in earlier layers. Each individual layer is more lightweight in terms of byte size than the final image.

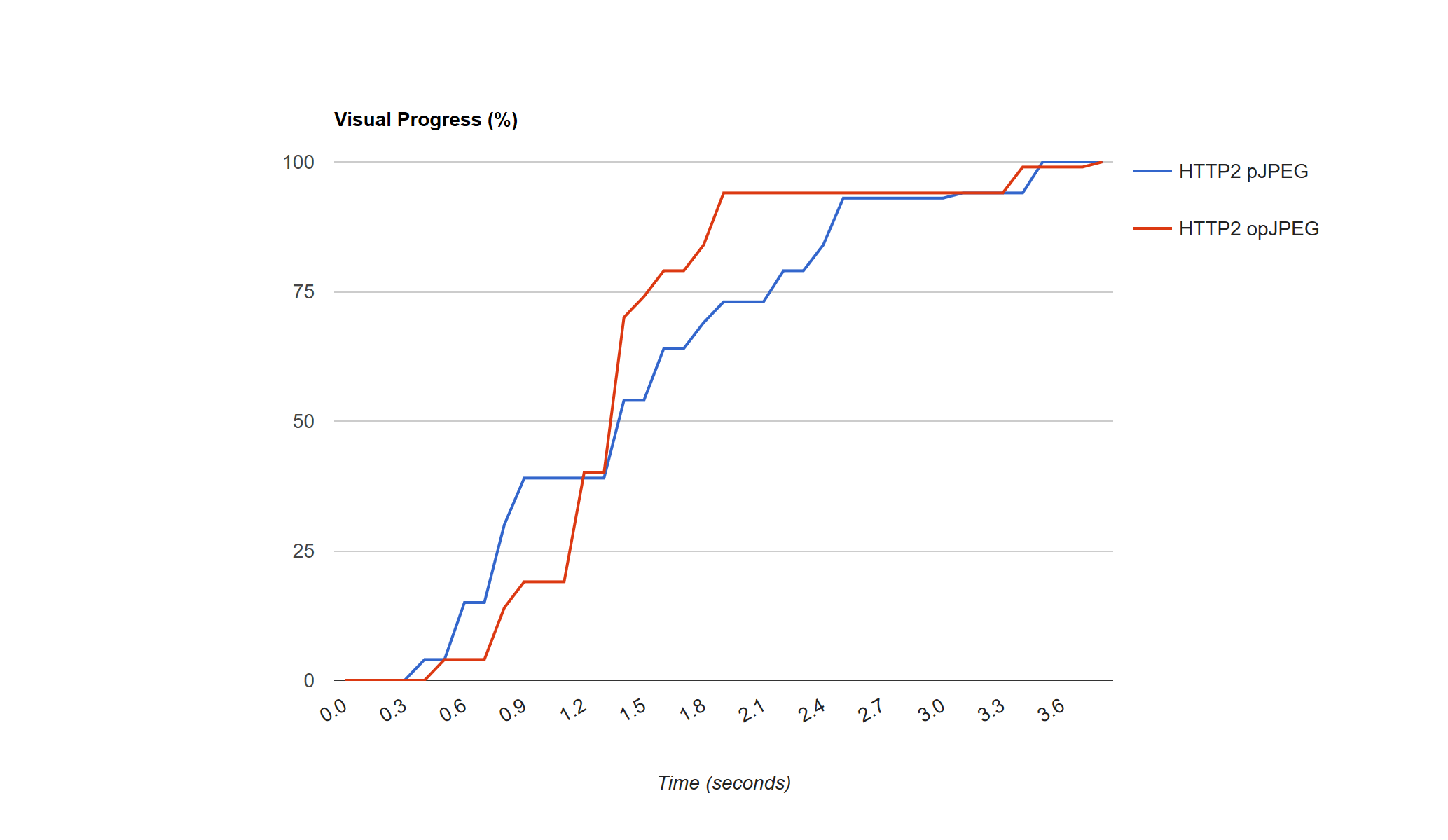

Since browsers loading website assets via HTTP2 Multiplexing will initiate almost all image downloads simultaneously, the initial, lightweight layers of progressive and interlaced images start rendering much more quickly than sequentially encoded images. Sequentially encoded images render in a windowblind manner: line by line until all image information has been shipped.

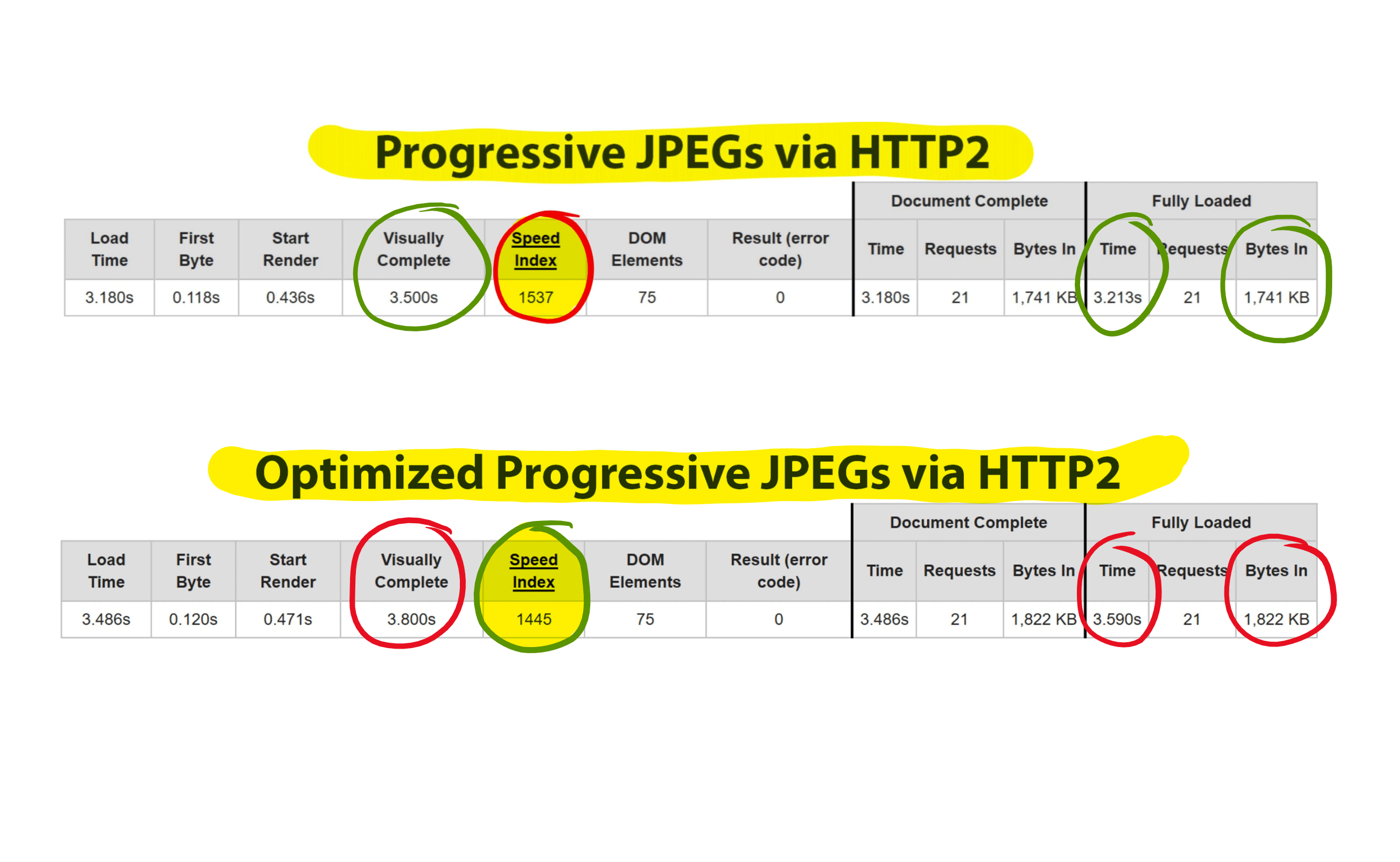

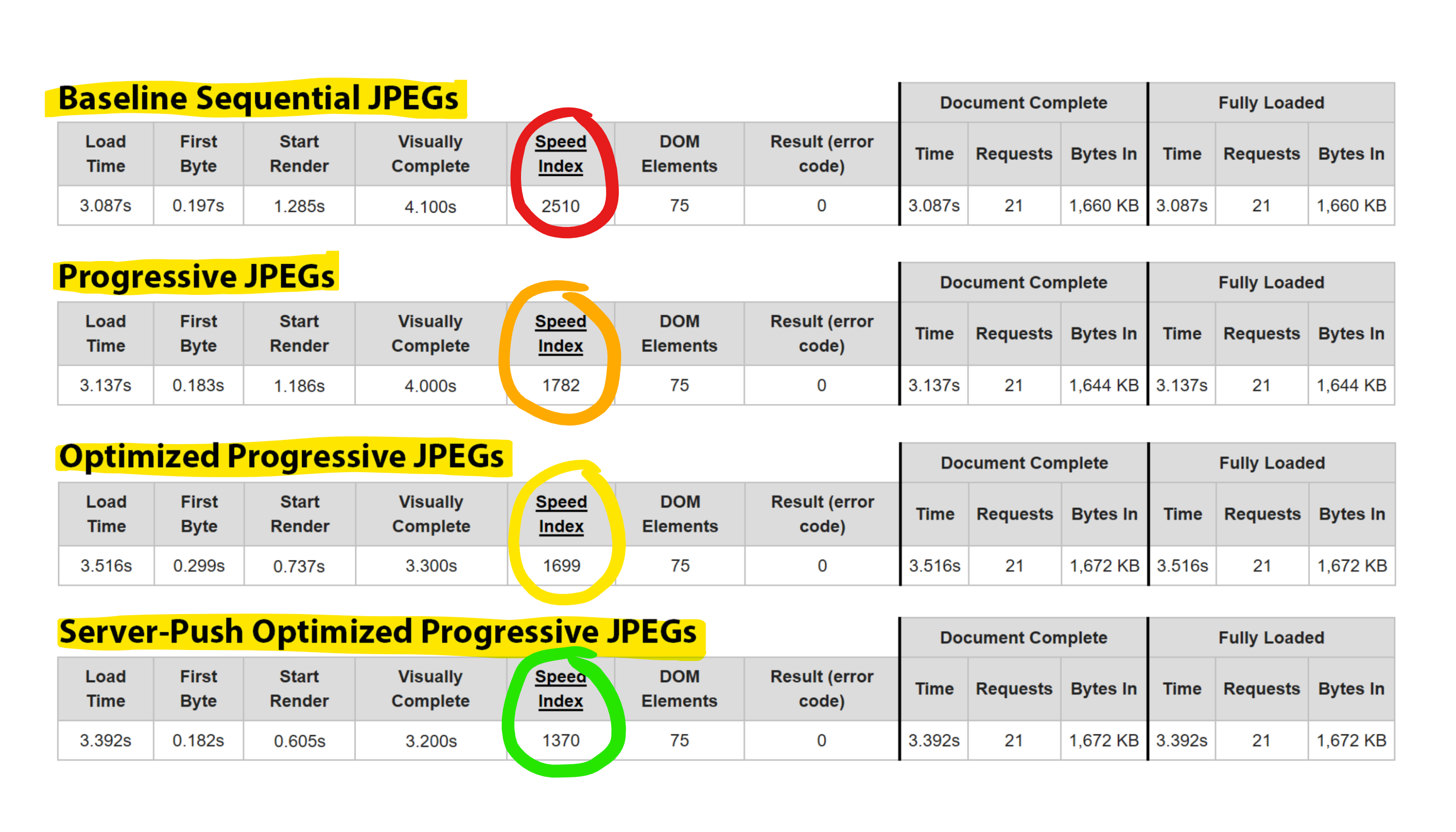

That perceived performance and the Speed Index benefit from delivering progressive JPEG scan layers via HTTP2 Multiplexing was already observed by Google’s John Mellor in 2012. He was experimenting with the SPDY protocol, a precursor to HTTP2. Today, we can improve on this discovery to make progressive images appear even faster:

That perceived performance and the Speed Index benefit from delivering progressive JPEG scan layers via HTTP2 Multiplexing was already observed by Google’s John Mellor in 2012. He was experimenting with the SPDY protocol, a precursor to HTTP2. Today, we can improve on this discovery to make progressive images appear even faster:

Take The Power Back! Or: The Scans File

Progressively encoded JPEGs contain ten scan layers by default. That means ten iterative layers of image information build on each other to deliver the final visual quality of the image. The first visible scan layer of a progressive JPEG is always highly pixelated and often black & white because it saves on color channel information. If you want to check out how each scan layer looks, use Frédéric Kayser’s “jsk” tool to split a progressive JPEG into its individual scan layers.

Progressively encoded JPEGs contain ten scan layers by default. That means ten iterative layers of image information build on each other to deliver the final visual quality of the image. The first visible scan layer of a progressive JPEG is always highly pixelated and often black & white because it saves on color channel information. If you want to check out how each scan layer looks, use Frédéric Kayser’s “jsk” tool to split a progressive JPEG into its individual scan layers.

Why ten layers? That’s the default setting inside all common JPEG encoders. It’s a compromise between byte size per scan layer, visual quality and helping the JPEG encoder achieve smaller total image file sizes during Huffman table optimizations.

Unlike PNGs, which use a fixed method called Adam7 encoding to create interlaced layers, we can supplement JPEG encoders with custom directives for scan layer creation: the “-scans” flag for JPEG encoders. You can use it like this with mozjpeg: “cjpeg -quality 75 -scans customscans.txt -outfile output.jpg input.jpg”. Now the JPEG encoder accepts a plaintext file containing your custom commands for scan layer creation.

Unlike PNGs, which use a fixed method called Adam7 encoding to create interlaced layers, we can supplement JPEG encoders with custom directives for scan layer creation: the “-scans” flag for JPEG encoders. You can use it like this with mozjpeg: “cjpeg -quality 75 -scans customscans.txt -outfile output.jpg input.jpg”. Now the JPEG encoder accepts a plaintext file containing your custom commands for scan layer creation.

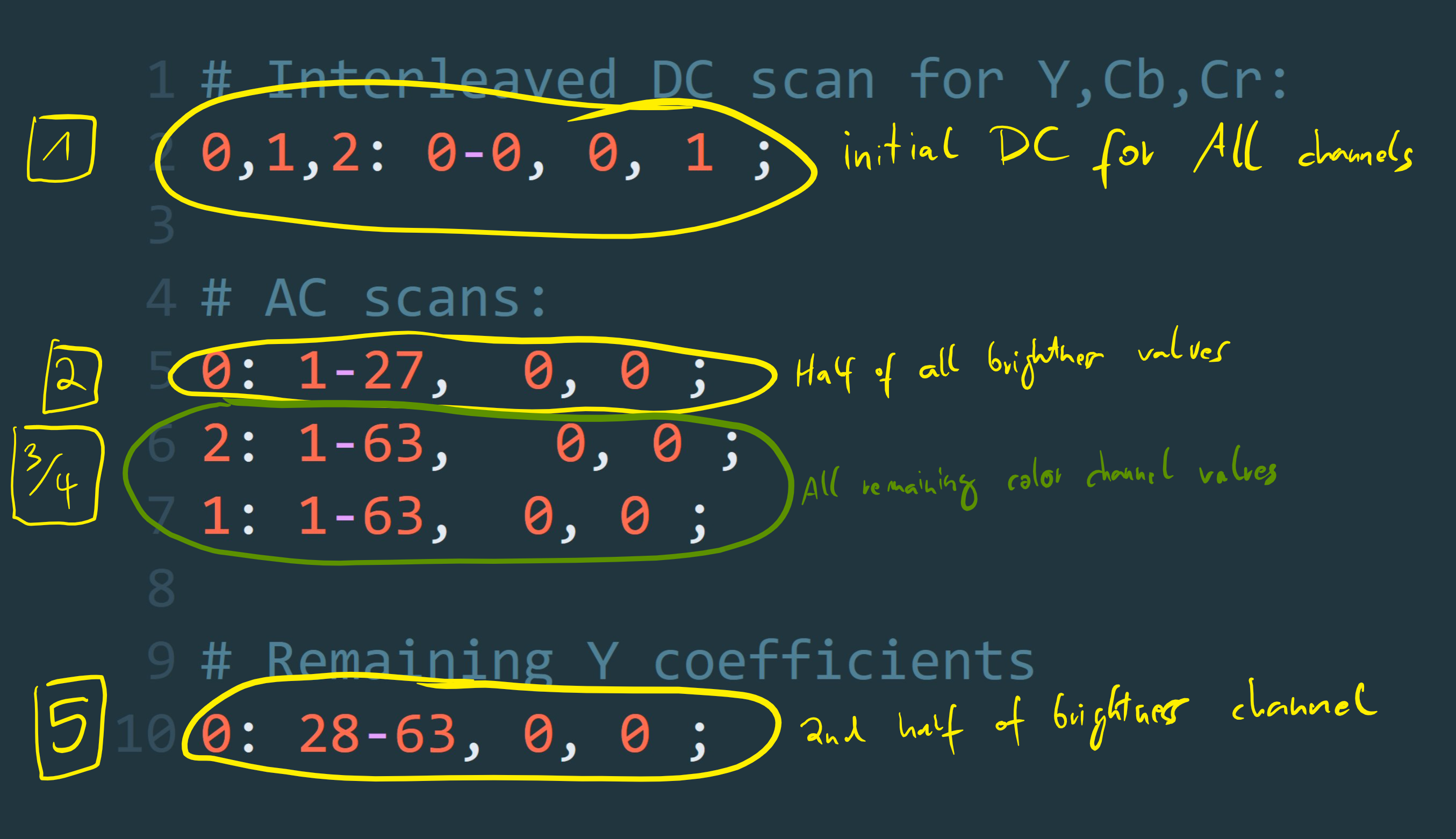

Each line in the scans file defines a new scan layer. They contain multiple parts of information on color channel, matrix index and lossiness.

The three channels are brightness (‘Y’), blue (‘Cb’) and red (‘Cr’), which respectively have the numbers 0,1 & 2 in the scans file. The matrix index in the scan file goes from 0 to 63, covering a 64-pixel block. (JPEG encoding has a native 8×8 block setting.)

Getting Creative

Our goal is to show meaningful image contents sooner while enabling browsers to lay out the site speedily. Our initial scan layer should therefore be lean but meaningful, followed by an as steep increase in perceived visual quality as possible.

Our goal is to show meaningful image contents sooner while enabling browsers to lay out the site speedily. Our initial scan layer should therefore be lean but meaningful, followed by an as steep increase in perceived visual quality as possible.

The custom scans file displayed here ensures a first scan layer with appropriate colors. At the second scan layer, we already have a highly acceptable preview. Scan layers three and four deliver the necessary color information: the red channel before blue channel since it is likely that red color information is more important to improve visuals, e.g. when showing faces. After the fourth scan layer, the image looks complete and the final fifth scan layer improves only fine high frequency details. These improvements are reflected in an ~6% better Speed Index, reflecting the perceived performance.

The above scans script is only one example of what is possible when customizing progressive JPEG encoding: using the same approach, you could recreate Guy Podjarny’s LQIP technique within progressive JPEGs as shown by Jon Sneyers.

Push! Push! Push!

HTTP2 offers another tool we may use for even faster delivery of image contents: Server Push. In supporting HTTP2-enabled web servers, it is possible to flag individual scan layers of progressive JPEGs with high priority and making the server push those scan layers into the client browsers’ Push cache even before the request for the respective image is initiated. Browsers then can lay out the page and render initial scan layers with the performance of a warmed cache, making users perceive the site’s images as rendering exceptionally fast.

Check out this brilliant article in this year’s Performance Advent Calendar to find out more about HTTP2 Server Push.

This technique should only be used strategically: find out which images are crucial for creating user engagement on your page, e.g. an emotion-evoking hero image or a product overview image, and only apply Server Push to the initial scan layers of those JPEG images. This will enable you to increase user engagement and thus successful conversions without harming overall site asset downloads.

Takeaways

- Multiple progressive or interlaced images render faster on HTTP2 thanks to Multiplexing

- Taking control of progressive JPEG creation may give users a better visual experience

- HTTP2 Server Push can increase perceived performance for important images

Credits: Thanks to Corinna Baldauf for proof & editing. Thanks to Colin Bendell and Yoav Weiss for inspiration & support.