tl;dr: lazy-load non-critical resources when a user interacts with UI requiring it

Your page may contain code or data for a component or resource that isn’t immediately necessary. For example, part of the user-interface a user doesn’t see unless they click or scroll on parts of the page. This can apply to many kinds of first-party code you author, but this also applies to third-party widgets such as video players or chat widgets where you typically need to click a button to display the main interface.

Loading these resources eagerly (i.e right away) can block the main thread if they are costly, pushing out how soon a user can interact with more critical parts of a page. This can impact interaction readiness metrics like First Input Delay, Total Blocking Time and Time to Interactive. Instead of loading these resources immediately, you can load them at a more opportune moment, such as:

- When the user clicks to interact with that component for the first time

- Scrolls the component into view

- or deferring load of that component until the browser is idle (via requestIdleCallback).

The different ways to load resources are, at a high-level:

- Eager – load resource right away (the normal way of loading scripts)

- Lazy (Route-based) – load when a user navigates to a route or component

- Lazy (On interaction) – load when the user clicks UI (e.g Show Chat)

- Lazy (In viewport) – load when the user scrolls towards the component

- Prefetch – load prior to needed, but after critical resources are loaded

- Preload – eagerly, with a greater level of urgency

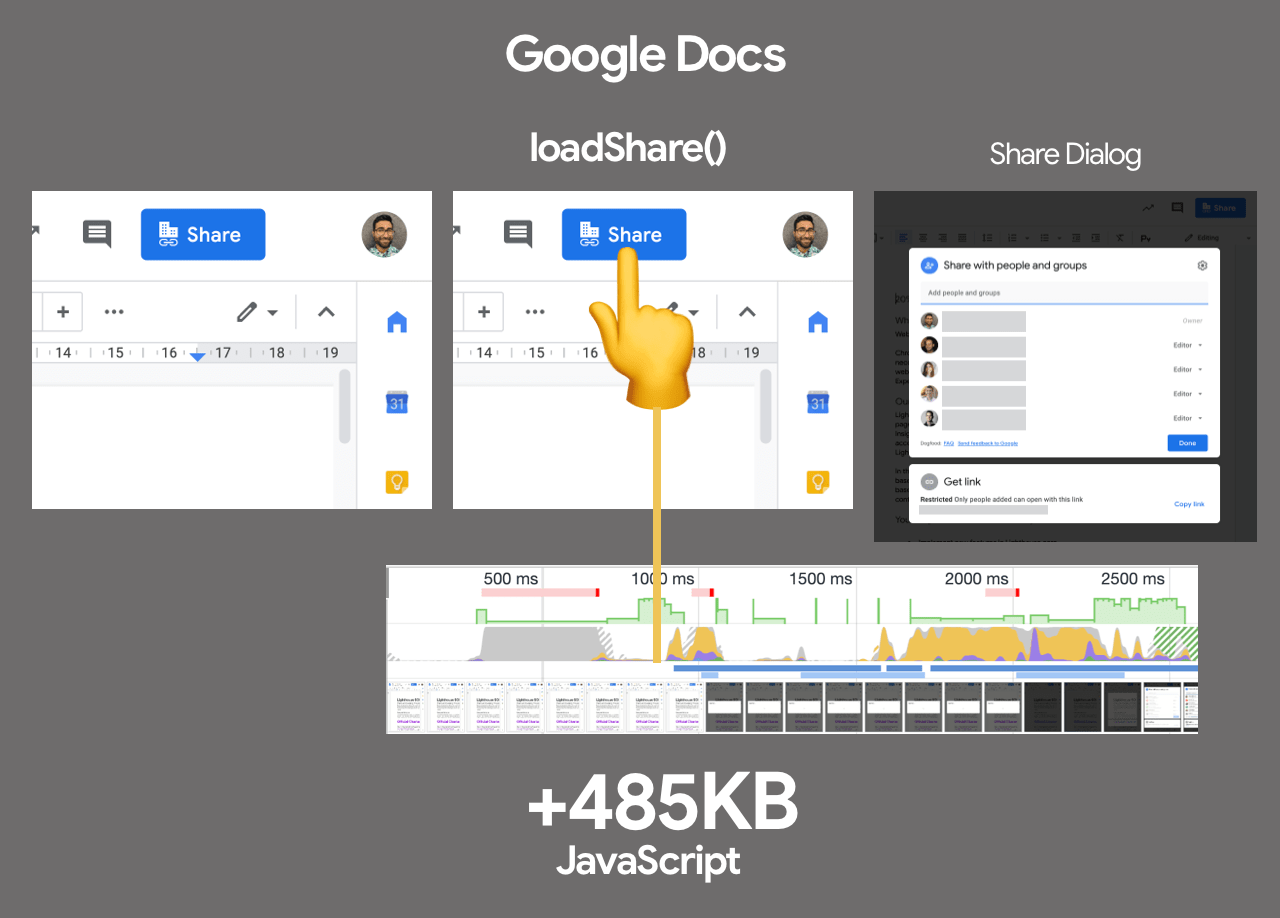

Lazily importing feature code on interaction is a pattern used in many contexts we will cover in this post. One place you may have used it before is Google Docs, where they save loading 500KB of script for the share feature by deferring its load until user-interaction.

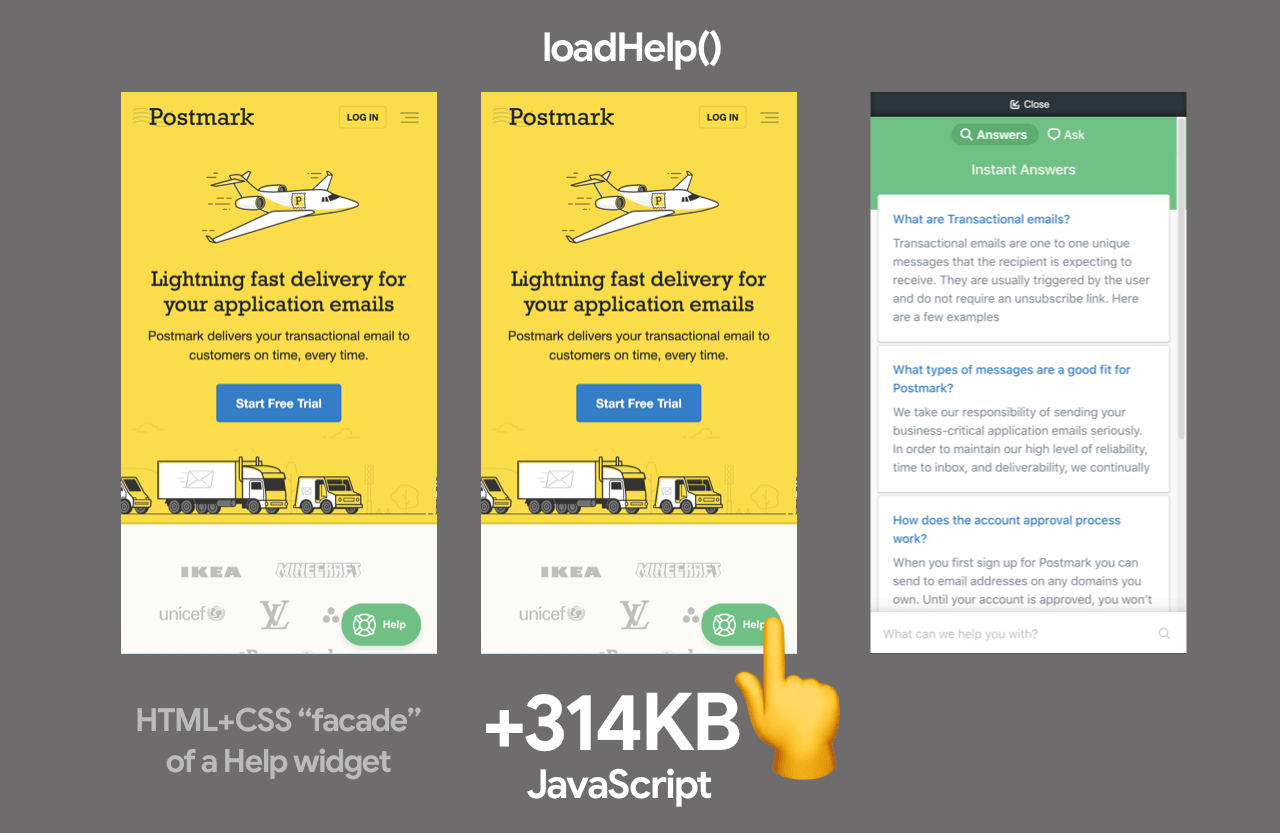

“Fake†loading third-party UI with a facade

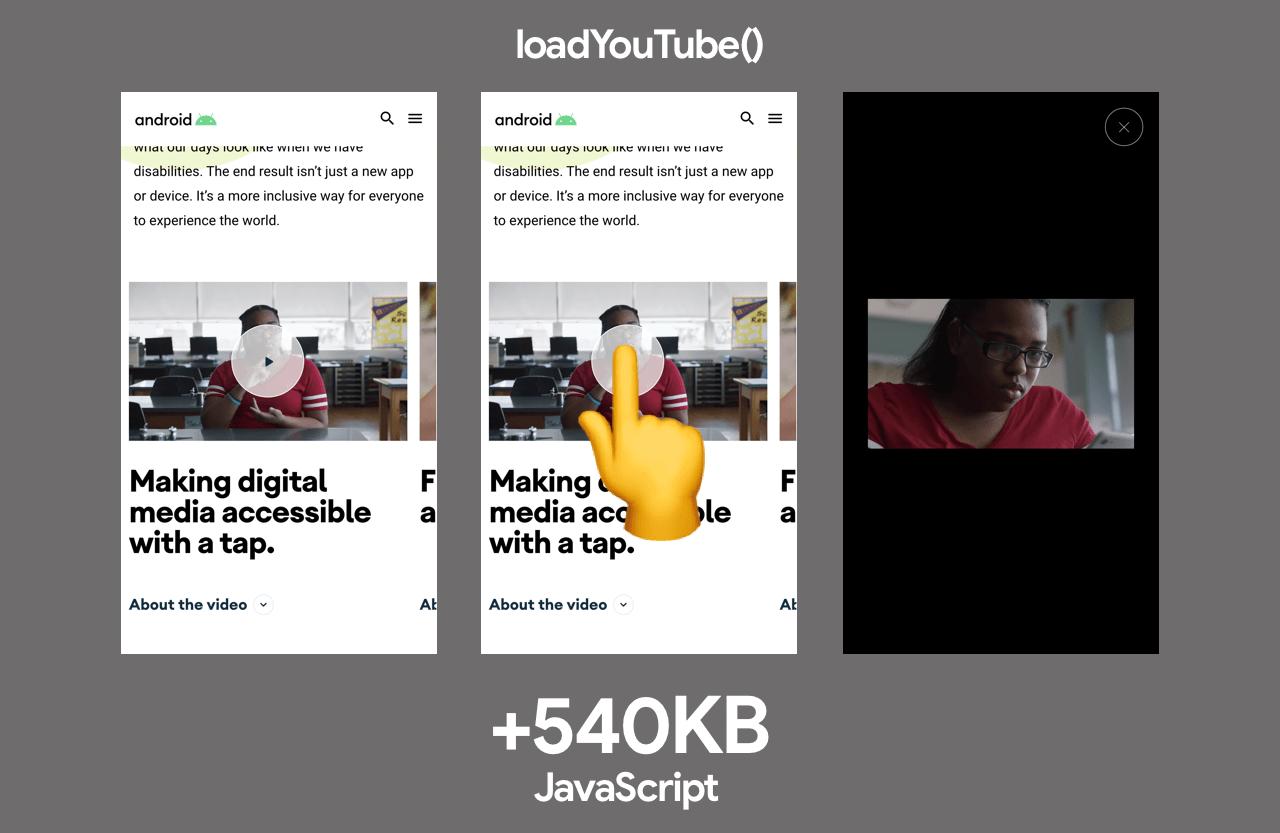

You might be importing a third-party script and have less control over what it renders or when it loads code. One option for implementing load-on-interaction is straight-forward: use a facade. A facade is a simple “preview†or “placeholder†for a more costly component where you simulate the basic experience, such as with an image or screenshot. It’s terminology we’ve been using for this idea on the Lighthouse team.

When a user clicks on the “preview†(the facade), the code for the resource is loaded. This limits users needing to pay the experience cost for a feature if they’re not going to use it. Similarly, facades can preconnect to necessary resources on hover.

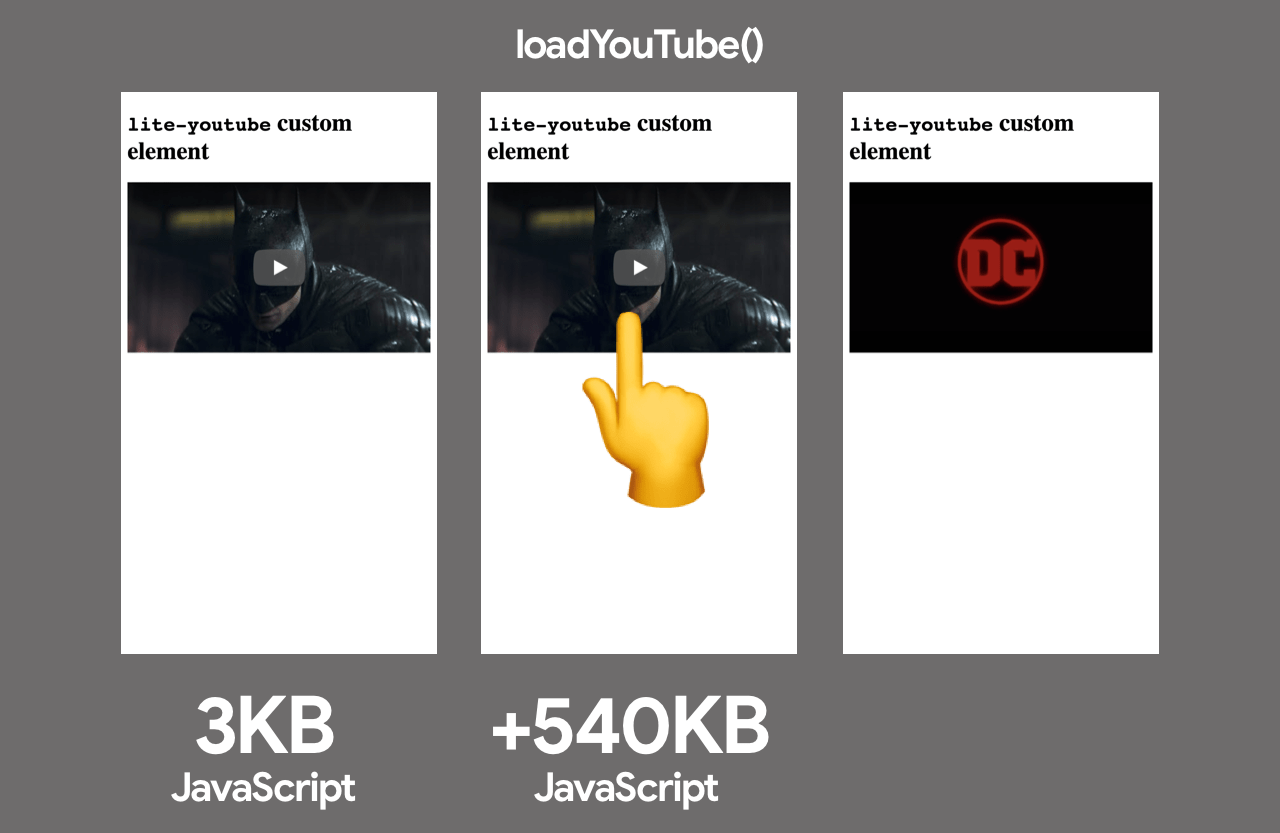

Video Player Embeds

A good example of a “facade†is the YouTube Lite Embed by Paul Irish. This provides a Custom Element which takes a YouTube Video ID and presents a minimal thumbnail and play button. Clicking the element dynamically loads the full YouTube embed code, meaning users who never click play don’t pay the cost of fetching and processing it.

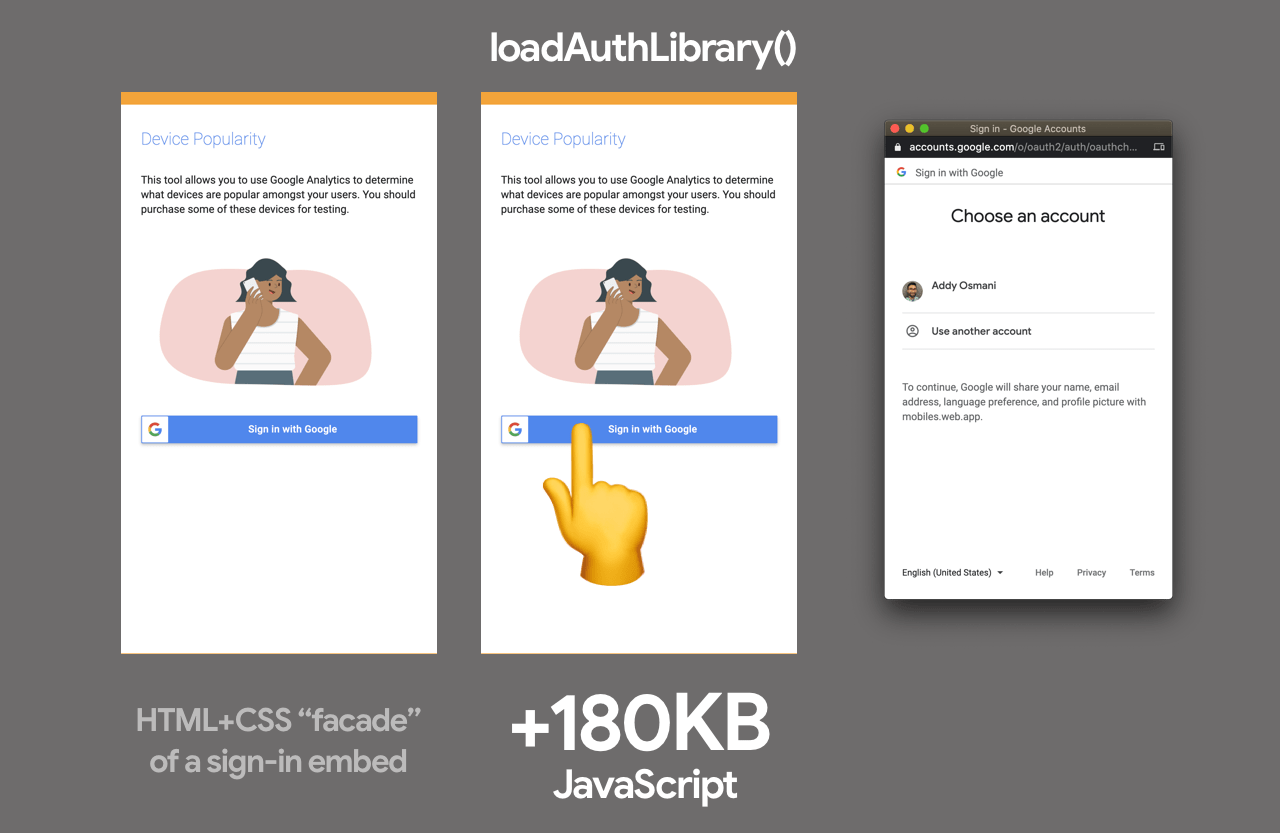

Authentication

Apps may need to support authentication with a service via a client-side JavaScript SDK. These can occasionally be large with heavy JS execution costs and I would rather not eagerly load them up front if a user isn’t going to login. Instead, I dynamically import authentication libraries when a user clicks on a “Login†button, keeping the main thread more free during initial load.

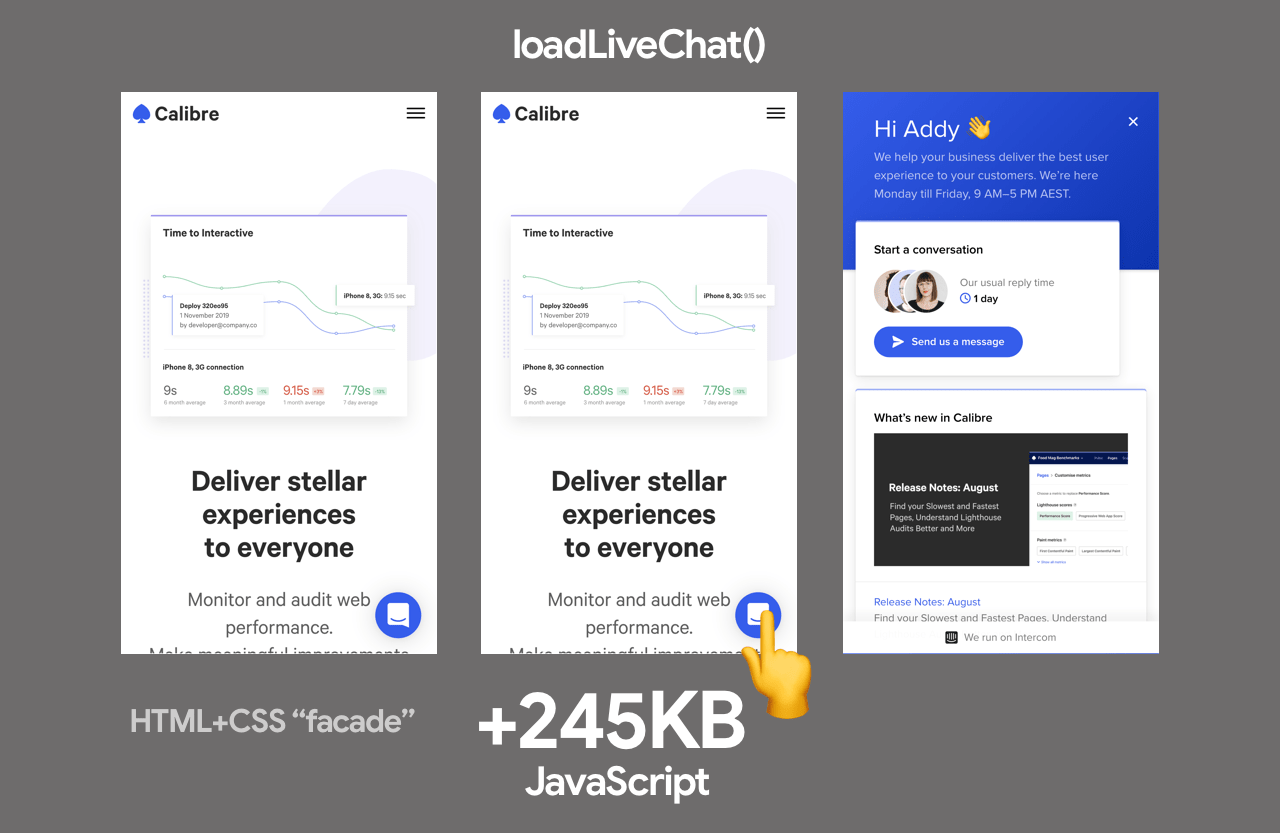

Chat widgets

Calibre app improved performance of their Intercom-based live chat by 30% through usage of a similar facade approach. They implemented a “fake†fast loading live chat button using just CSS and HTML, which when clicked would load their Intercom bundles.

Others

Ne-digital used a React library for animated scrolling back to the top of a page when a user clicks on a “scroll to top†button. Rather than eagerly loading the react-scroll dependency for this, they load it on interaction with the button, saving ~7KB:

handleScrollToTop() {

import('react-scroll').then(scroll => {

scroll.animateScroll.scrollToTop({

})

})

}

How do you import-on-interaction?

Vanilla JavaScript

In JavaScript, dynamic import() enables lazy-loading modules and returns a promise and can be quite powerful when applied correctly. Below is an example where dynamic import is used in a button event listener to import the lodash.sortby module and then use it.

const btn = document.querySelector('button');

btn.addEventListener('click', e => {

e.preventDefault();

import('lodash.sortby')

.then(module => module.default)

.then(sortInput()) // use the imported dependency

.catch(err => { console.log(err) });

});

Prior to dynamic import or for use-cases it doesn’t fit as well, I would dynamically inject scripts in my page using a Promise-based script loader (see here for full implementation that demonstrates a sign-in facade):

const loginBtn = document.querySelector('#login');

loginBtn.addEventListener('click', () => {

const loader = new scriptLoader();

loader.load([

'//apis.google.com/js/client:platform.js?onload=showLoginScreen'

]).then(({length}) => {

console.log(`${length} scripts loaded!`);

});

});

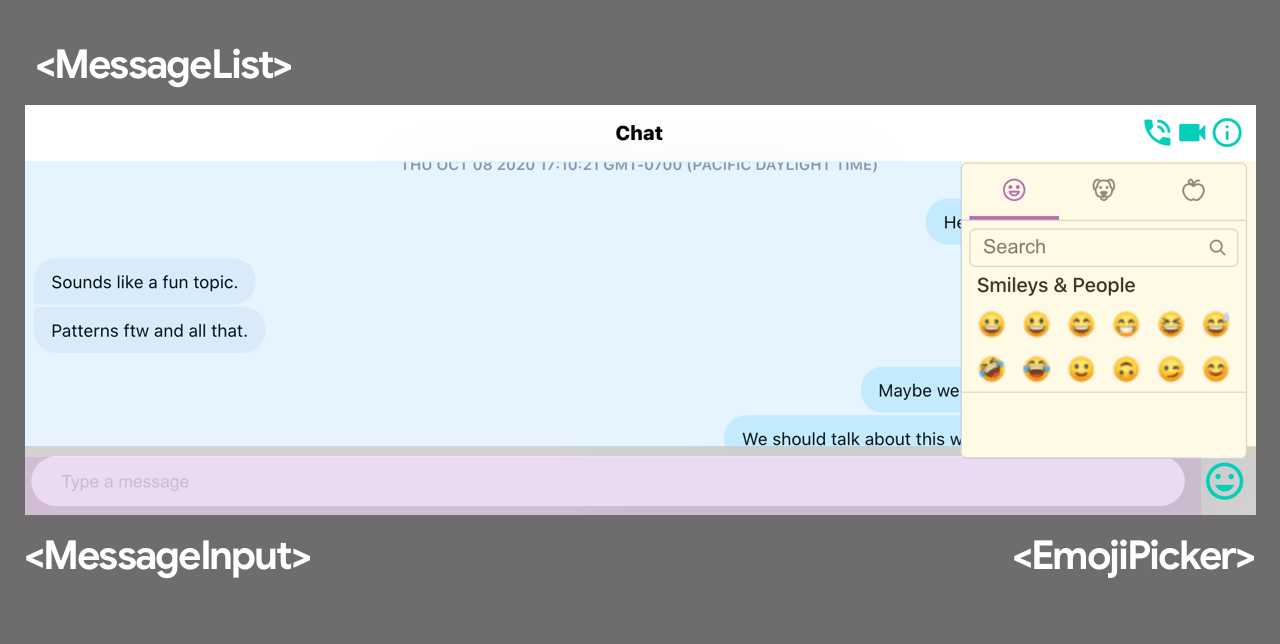

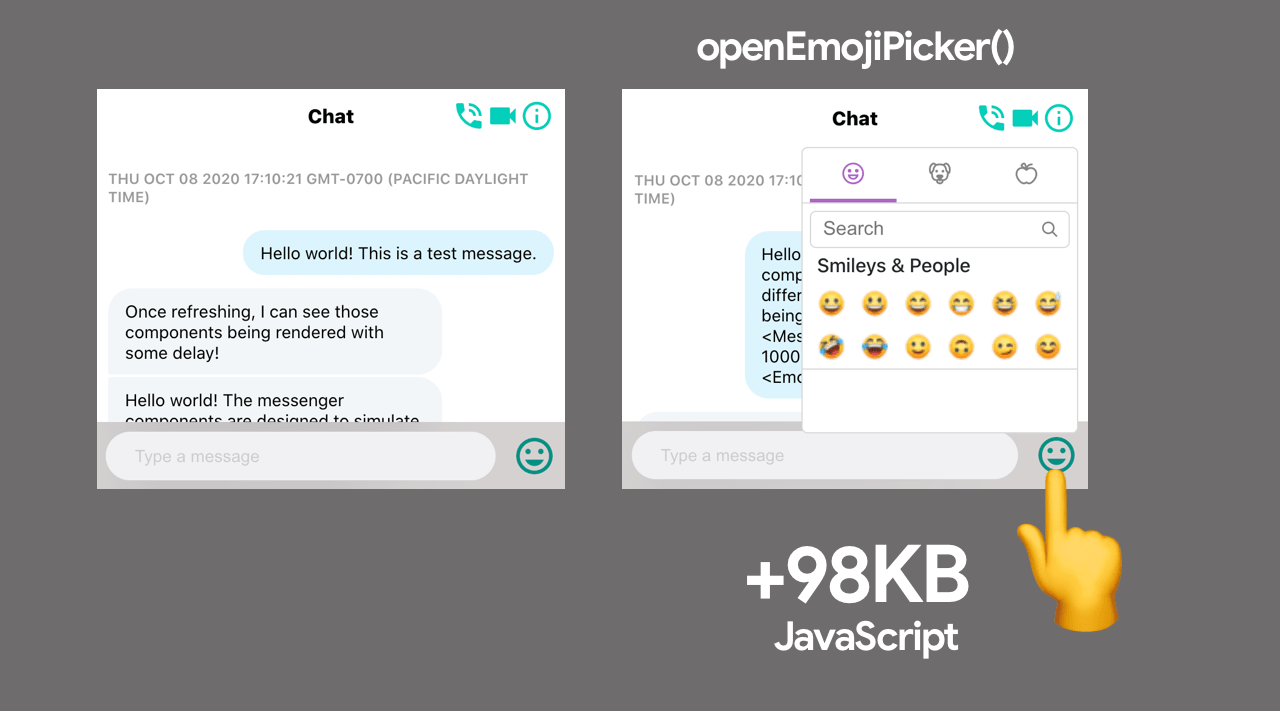

React

Let’s imagine we have a Chat application which has a <MessageList>, <MessageInput> and an <EmojiPicker> component (powered by emoji-mart, which is 98KB minified and gzipped). It can be common to eagerly load all of these components on initial page-load.

import MessageList from './MessageList';

import MessageInput from './MessageInput';

import EmojiPicker from './EmojiPicker';

const Channel = () => {

...

return (

<div>

<MessageList />

<MessageInput />

{emojiPickerOpen && <EmojiPicker />}

</div>

);

};

React.lazy method makes it easy to code-split a React application on a component level using dynamic imports. The React.lazy function provides a built-in way to separate components in an application into separate chunks of JavaScript with very little legwork. You can then take care of loading states when you couple it with the Suspense component.

import React, { lazy, Suspense } from 'react';

import MessageList from './MessageList';

import MessageInput from './MessageInput';

const EmojiPicker = lazy(

() => import('./EmojiPicker')

);

const Channel = () => {

...

return (

<div>

<MessageList />

<MessageInput />

{emojiPickerOpen && (

<Suspense fallback={<div>Loading...</div>}>

<EmojiPicker />

</Suspense>

)}

</div>

);

};

We can extend this idea to only import code for the Emoji Picker component when the Emoji icon is clicked in a <MessageInput>, rather than eagerly when the application initially loads:

import React, { useState, createElement } from 'react';

import MessageList from './MessageList';

import MessageInput from './MessageInput';

import ErrorBoundary from './ErrorBoundary';

const Channel = () => {

const [emojiPickerEl, setEmojiPickerEl] = useState(null);

const openEmojiPicker = () => {

import(/* webpackChunkName: "emoji-picker" */ './EmojiPicker')

.then(module => module.default)

.then(emojiPicker => {

setEmojiPickerEl(createElement(emojiPicker));

});

};

const closeEmojiPickerHandler = () => {

setEmojiPickerEl(null);

};

return (

<ErrorBoundary>

<div>

<MessageList />

<MessageInput onClick={openEmojiPicker} />

{emojiPickerEl}

</div>

</ErrorBoundary>

);

};

Vue

In Vue.js, a similar import-on-interaction pattern can be accomplished in a few different ways. One way is to dynamically import the Emojipicker Vue component using dynamic import wrapped in a function i.e () => import("./Emojipicker"). Typically doing this will have Vue.js lazy-load the component when it needs to be rendered.

We can then gate lazy-loading behind a user-interaction. Using a conditional v-if on the picker’s parent div which is toggled by clicking a button, we can then both conditionally fetch and render the Emojipicker component when the user clicks.

<template>

<div>

<button @click="show = true">Load Emoji Picker</button>

<div v-if="show">

<emojipicker></emojipicker>

</div>

</div>

</template>

<script>

export default {

data: () => ({ show: false }),

components: {

Emojipicker: () => import('./Emojipicker')

}

};

</script>

The import-on-interaction pattern should be possible with most frameworks and libraries that support dynamic component loading, including Angular.

Import-on-interaction for first-party code as part of progressive loading

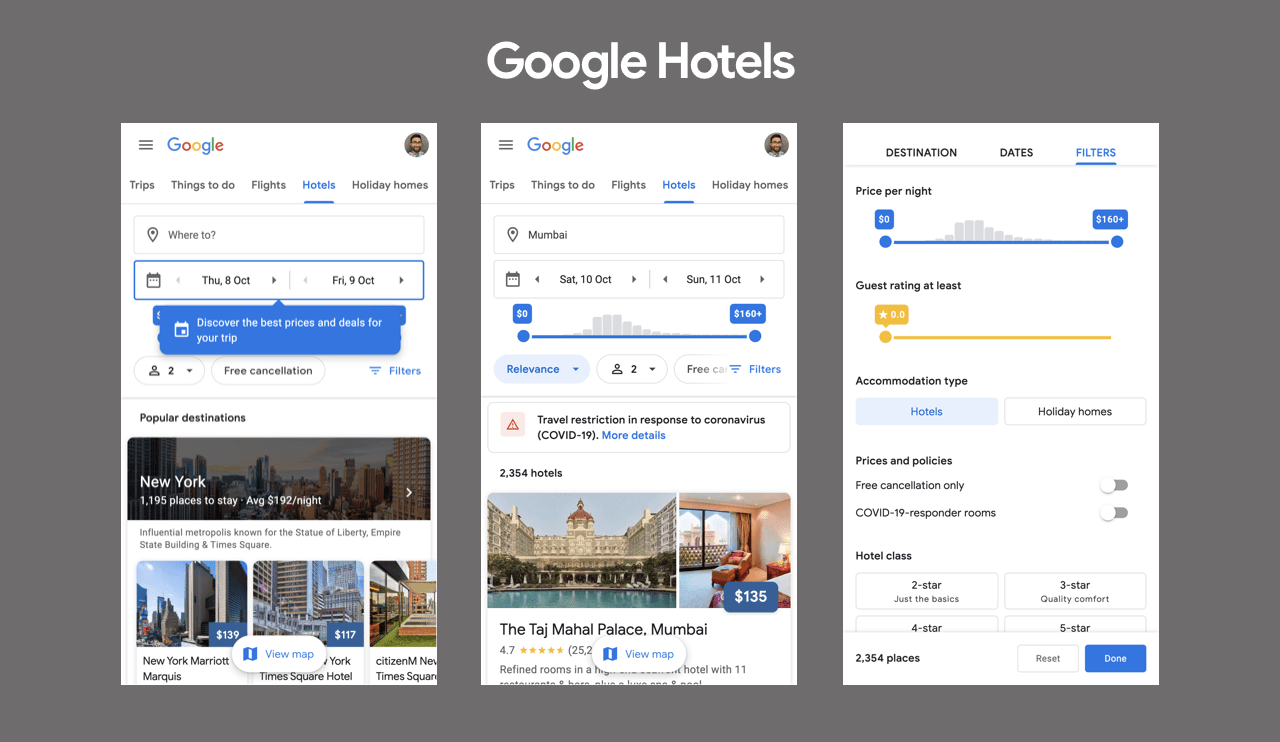

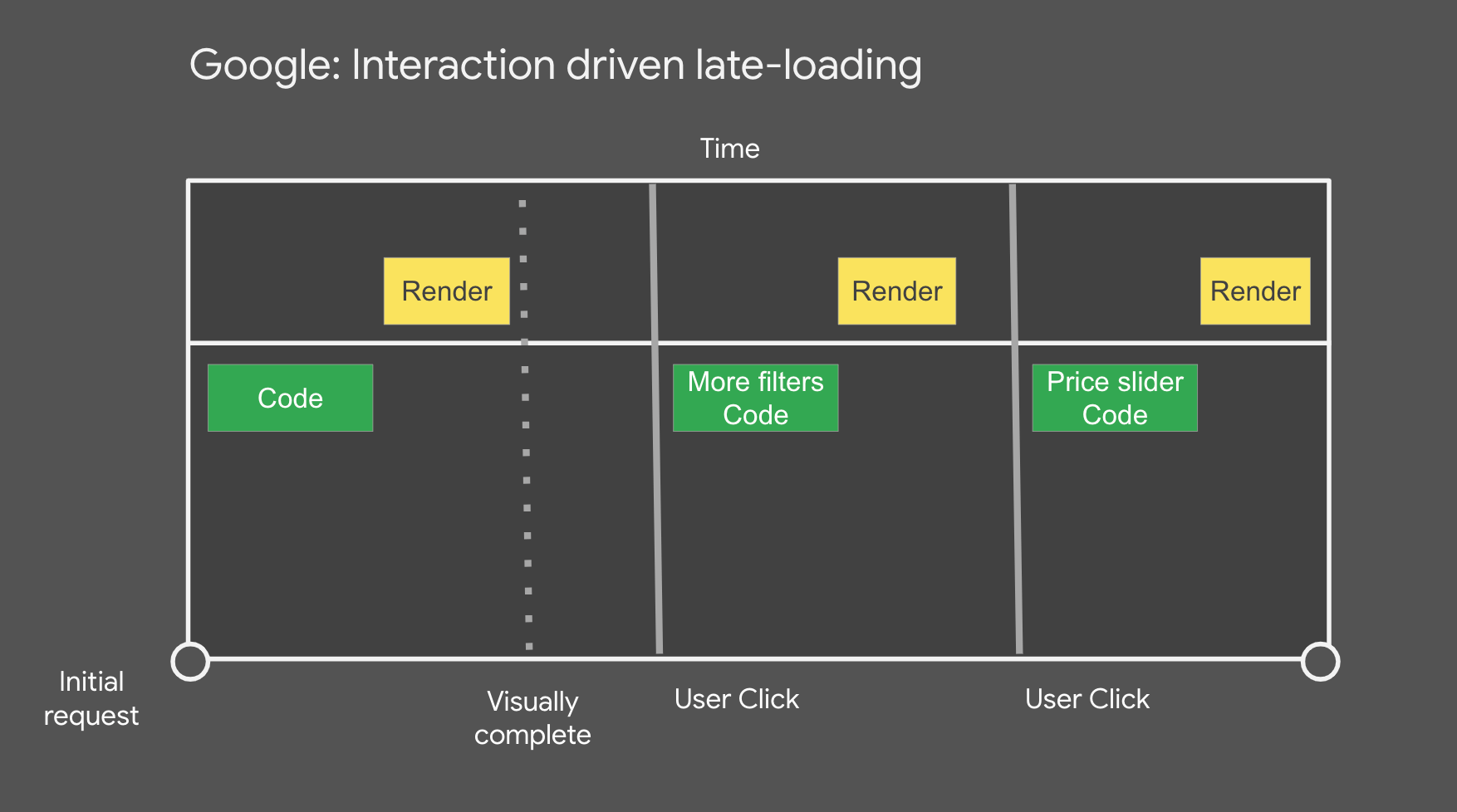

Loading code on interaction also happens to be a key part of how Google handles progressive loading in large applications like Flights and Photos. To illustrate this, let’s take a look at an example previously presented by Shubhie Panicker.

Imagine a user is planning a trip to Mumbai, India and they visit Google Hotels to look at prices. All of the resources needed for this interaction could be loaded eagerly upfront, but if a user hasn’t selected any destination, the HTML/CSS/JS required for the map would be unnecessary.

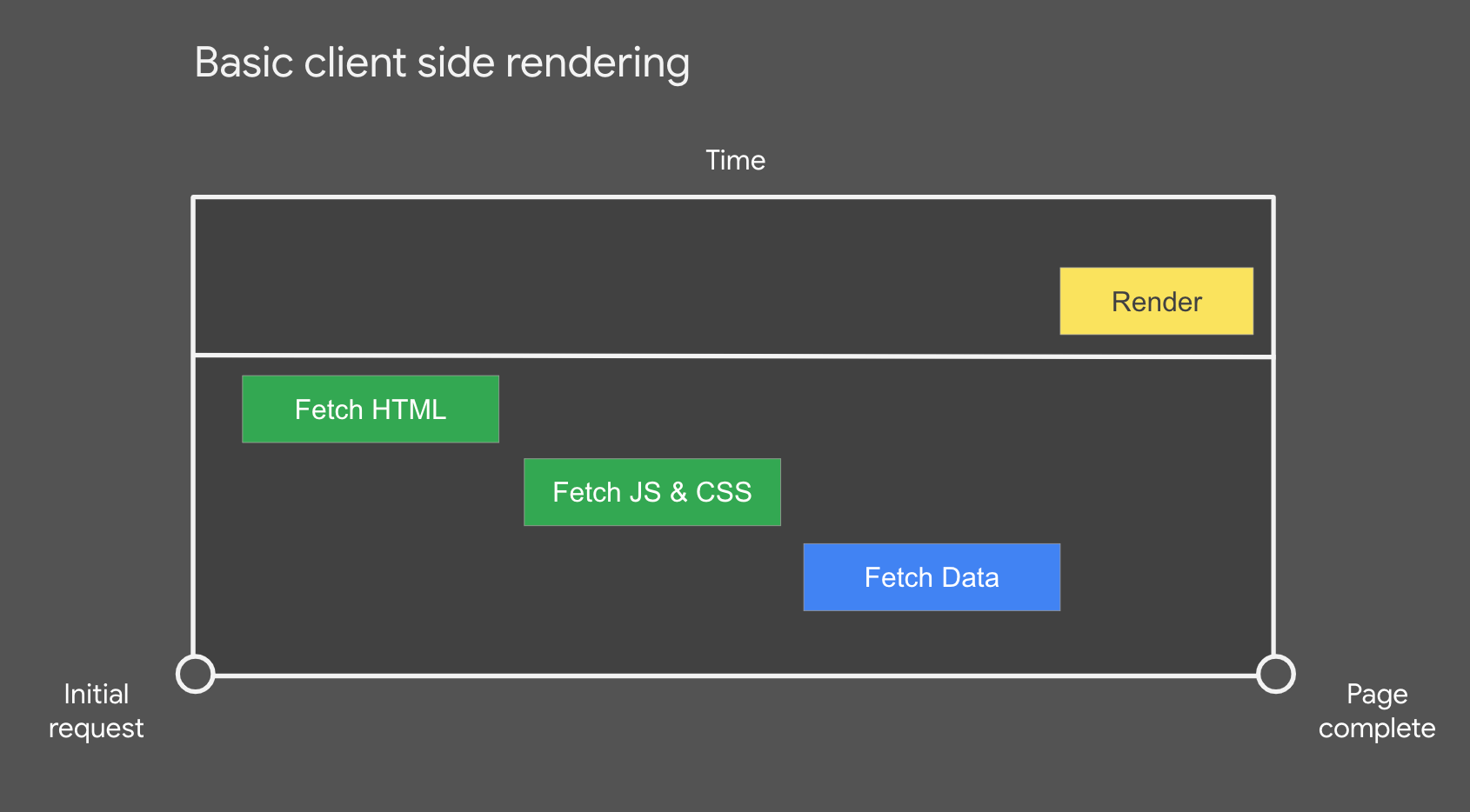

Next, imagine this experience moved to server-side rendering (SSR). We would allow the user to get a visually complete page sooner, which is great, however it wouldn’t be interactive until the data is fetched from the server and the client framework completes hydration.

SSR can be an improvement, but the user may have an uncanny valley experience where the page looks ready, but they are unable to tap on anything. Sometimes this is referred to as rage clicks as users tend to click over and over again repeatedly in frustration.

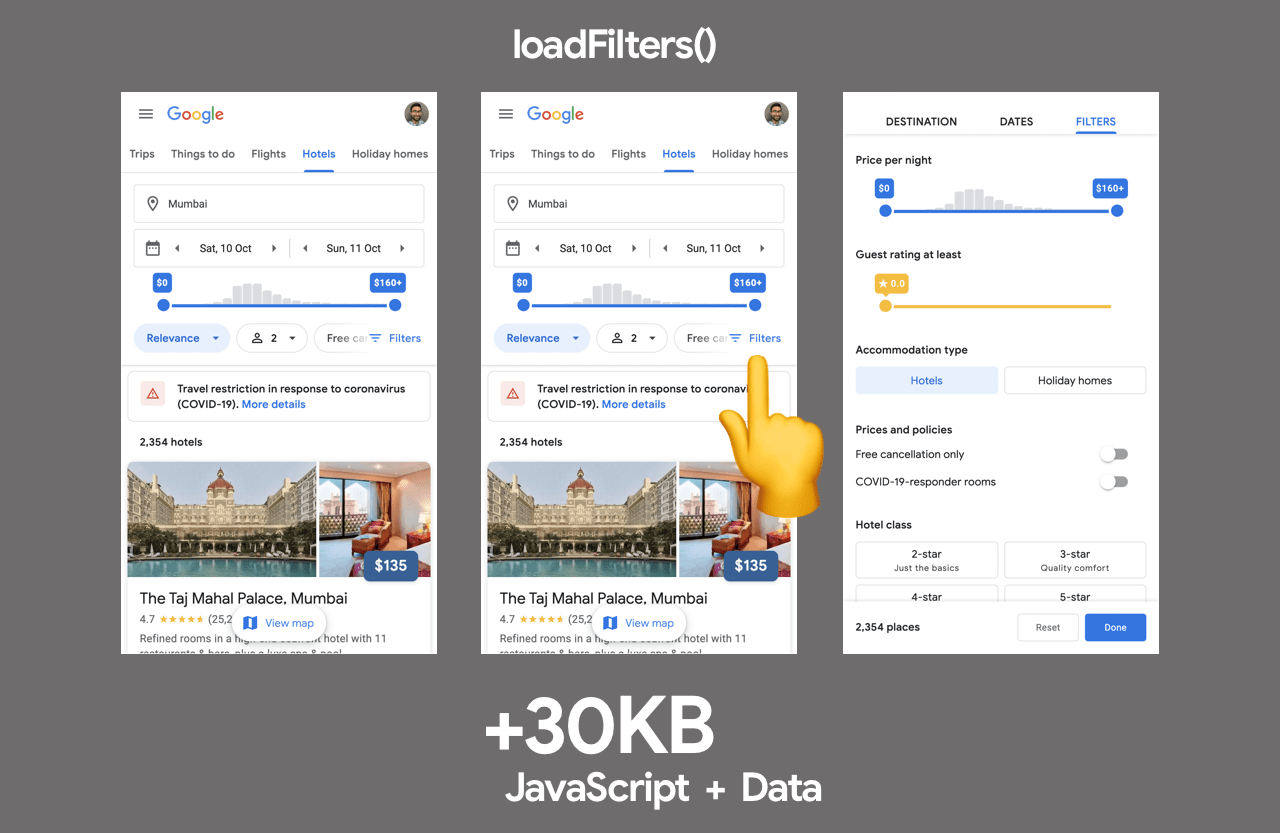

Returning to the Google Hotels search example, if we zoom in to the UI a little we can see that when a user clicks on “more filters†to find exactly the right hotel, the code required for that component is downloaded.

Only very minimal code is downloaded initially and beyond this, user interaction dictates which code is sent down when.

Let’s take a closer look at this loading scenario.

There are a number of important aspects to interaction-driven late-loading:

- First, we download the minimal code initially so the page is visually complete quickly.

- Next, as the user starts interacting with the page we use those interactions to determine which other code to load. For example loading the code for the “more filters†component.

- This means code for many features on the page are never sent down to the browser, as the user didn’t need to use them.

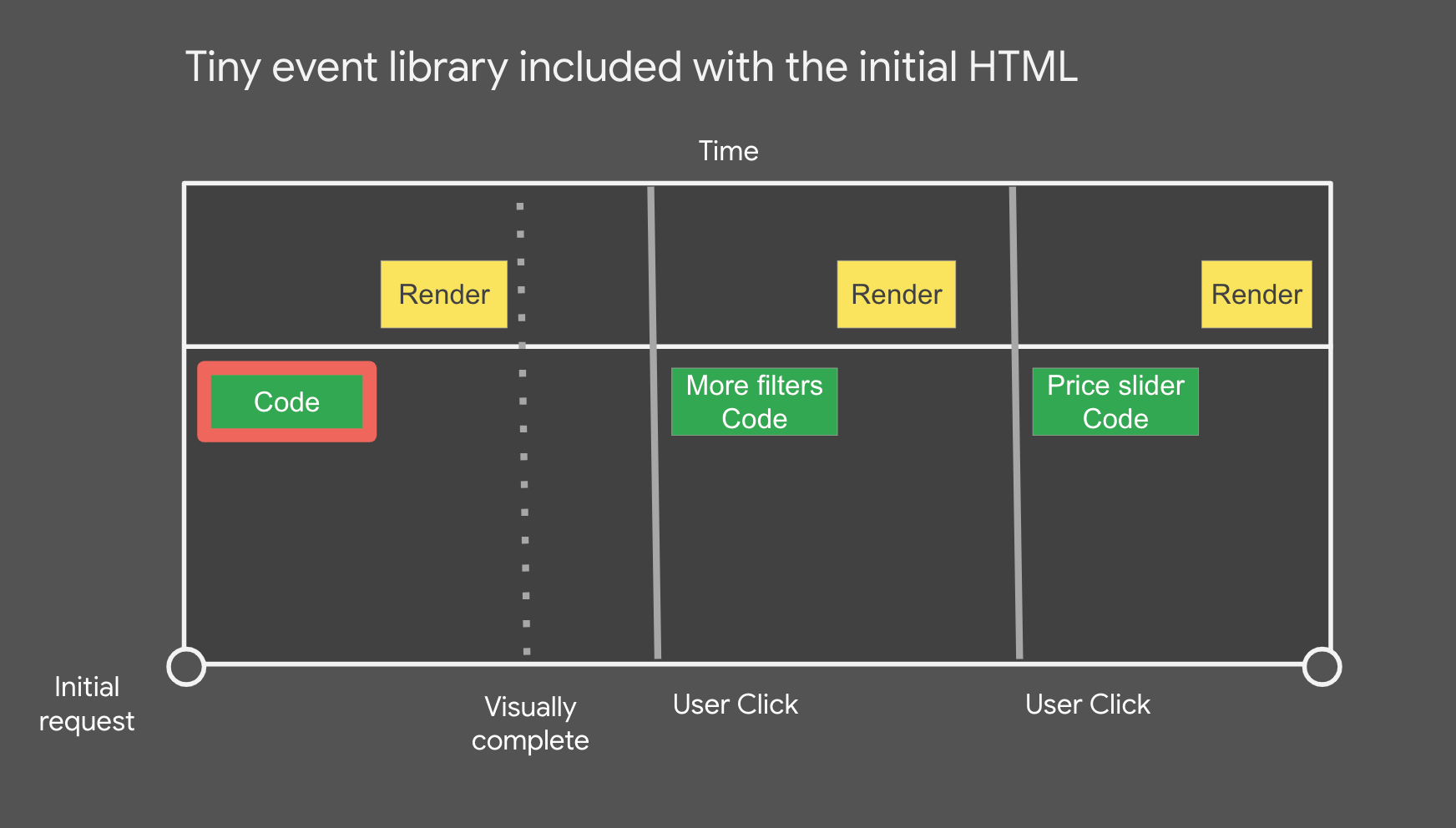

How do we avoid losing early clicks?

In the framework stack used by these Google teams, we can track clicks early because the first chunk of HTML includes a small event library (JSAction) which tracks all clicks before the framework is bootstrapped. The events are used for two things:

- Triggering download of component code based on user interactions

- Replaying user interactions when the framework finishes bootstrapping

Other potential heuristics one could use include, loading component code:

- A period after idle time

- On user mouse hover over the relevant UI/button/call to action

- Based on a sliding scale of eagerness based on browser signals (e.g network speed, Data Saver mode etc).

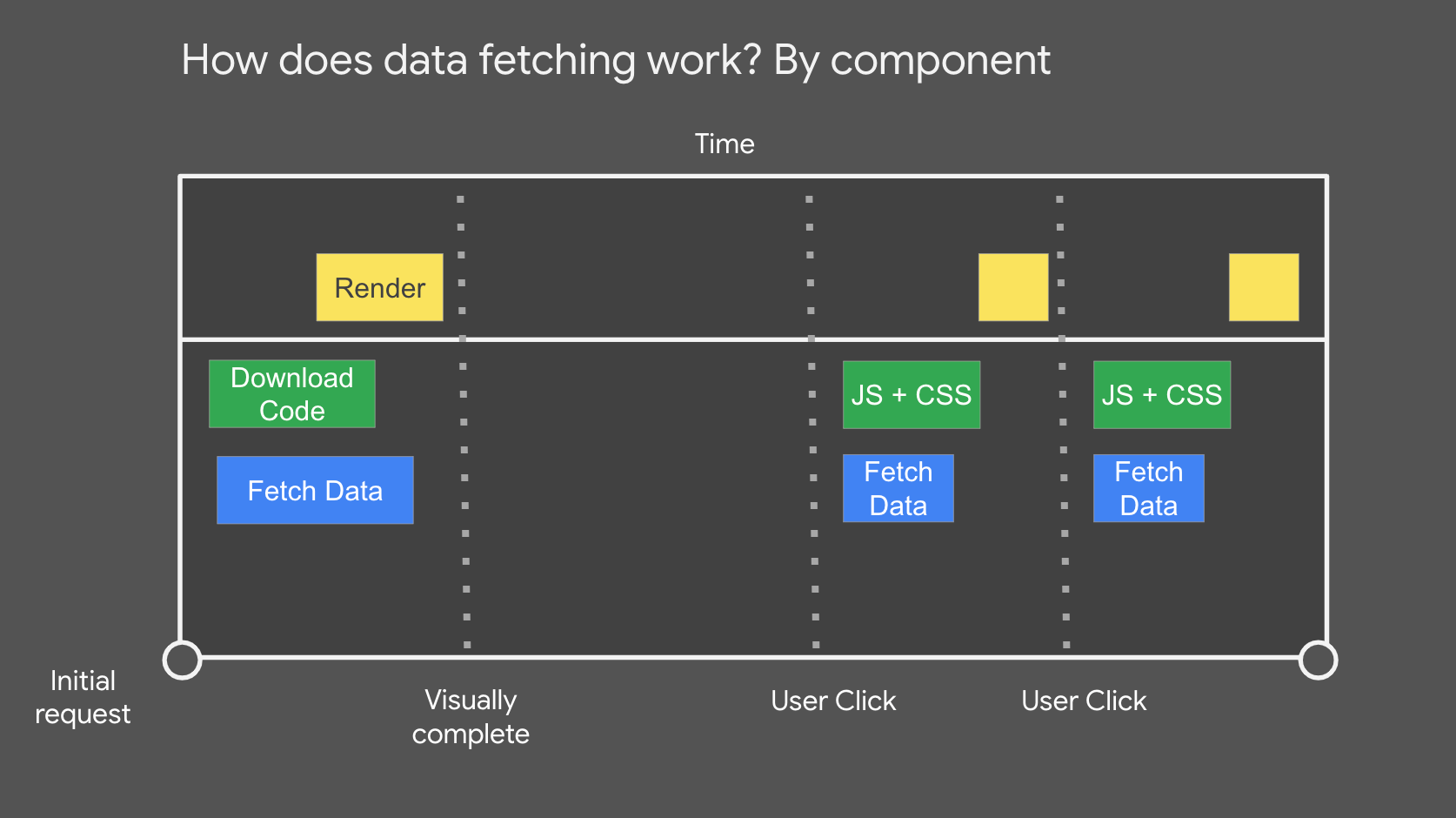

What about data?

The initial data which is used to render the page is included in the initial page’s SSR HTML and streamed. Data that is late loaded is downloaded based on user interactions as we know what component it goes with.

This completes the import-on-interaction picture with data-fetching working similar to how CSS and JS function. As the component is aware of what code and data it needs, all of its resources are never more than a request away.

This functions as we create a graph of components and their dependencies during build time. The web application is able to refer to this graph at any point and quickly fetch the resources (code and data) needed for any component. It also means we code-split based on the component rather than the route.

For a walkthrough of the above example, see Elevating the Web Platform with the JavaScript Community.

Trade-offs

Shifting costly work closer to user-interaction can optimize how quickly pages initially load, however the technique is not without trade-offs.

What happens if it takes a long time to load a script after the user clicks?

In the Google Hotels example, small granular chunks minimize the chance a user is going to wait long for code and data to fetch and execute. In some of the other cases, a large dependency may indeed introduce this concern on slower networks.

One way to reduce the chance of this happening is to better break-up the loading of, or prefetch these resources after critical content in the page is done loading. I’d encourage measuring the impact of this to determine how much it’s a real application in your apps.

What about lack of functionality before user interaction?

Another trade-off with facades is a lack of functionality prior to user interaction. An embedded video player for example will not be able to autoplay media. If such functionality is key, you might consider alternative approaches to loading the resources, such as lazy-loading these third-party iframes on the user scrolling them into view rather than deferring load until interaction.

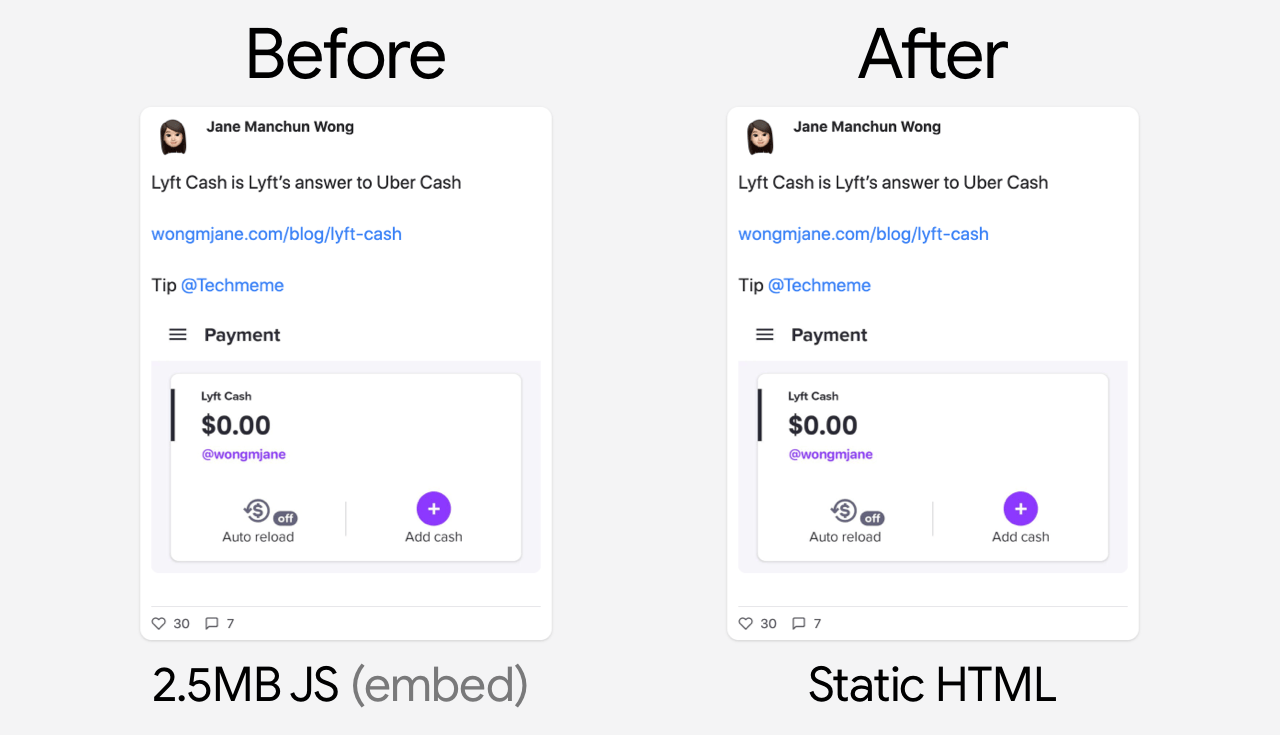

Replacing interactive embeds with a static variant

We have discussed the import-on-interaction pattern and progressive loading, but what about going entirely static for the embeds use-case?.

The final rendered content from an embed may be needed immediately in some cases e.g a social media post that is visible in the initial viewport. This can also introduce its own challenges when the embed brings in 2-3MB of JavaScript. Because the embed content is needed right away, lazy-loading and facades may be less applicable.

If optimizing for performance, it’s possible to entirely replace an embed with a static variant that looks similar, linking out to a more interactive version (e.g the original social media post). At build time, the data for the embed can be pulled in and transformed into a static HTML version.

This is the approach @wongmjane leveraged on their blog for one type of social media embed, improving both page load performance and removing the Cumulative Layout Shift experienced due to the embed code enhancing the fallback text, causing layout shifts.

While static replacements can be good for performance, they do often require doing something custom so keep this in mind when evaluating your options.

Conclusions

First-party JavaScript often impacts the interaction readiness of modern pages on the web, but it can often get delayed on the network behind non-critical JS from either first or third-party sources that keep the main thread busy.

In general, avoid synchronous third-party scripts in the document head and aim to load non-blocking third-party scripts after first-party JS has finished loading. Patterns like import-on-interaction give us a way to defer the loading of non-critical resources to a point when a user is much more likely to need the UI they power.

With special thanks to Shubhie Panicker, Connor Clark, Patrick Hulce, Anton Karlovskiy and Adam Raine for their input.