Robin Marx is a Web Performance and network protocol researcher at Hasselt University, Belgium. He is mainly looking into HTTP/3 and QUIC performance, and develops the qlog and qvis tools to make this easier. In a previous life he was a multiplayer game programmer and co-founder of LuGus Studios. YouTube videos of Robin are either humoristic technical talks or him hitting other people with longswords.

Head-of-Line Blocking in QUIC and HTTP/3: The Details

As you may have heard, after 4 years of work, the new HTTP/3 and QUIC protocols are finally approaching official standardization. Preview versions are now available for testing in servers and browsers alike.

HTTP/3 is promising major performance improvements compared to HTTP/2, mainly because it changes its underlying transport protocol from TCP to QUIC over UDP. In this post, we’ll be taking an in-depth look at just one of these improvements, namely the removal of the “Head-of-Line blocking” (HOL blocking) problem. This is useful because I’ve read a lot of misconceptions on what this actually means and how much it helps in practice. Solving HOL blocking was also one of the main motivations behind not just HTTP/3 and QUIC but also HTTP/2, so it gives a fantastic insight in the reasons for protocol evolution as well.

I’ll first introduce the problem and then track different forms of it throughout HTTP’s history. We will also look how it interacts with other systems like prioritization and congestion control. The goal is to help people make correct assumptions about HTTP/3’s performance improvements, which (spoiler) might not be as amazing as sometimes claimed in marketing materials.

Table of contents:

- What is Head-of-Line blocking?

- HOL blocking in HTTP/1.1

- HOL blocking in HTTP/2 over TCP

- HOL blocking in HTTP/3 over QUIC

- Summary and Conclusion

Bonus content:

- Bonus: HTTP/1.1 pipelining

- Bonus: TLS HOL blocking

- Bonus: Transport Congestion Control

- Bonus: Is multiplexing important or not?

What is Head-of-Line blocking?

It’s difficult to give you a single technical definition of HOL blocking, as this blogpost alone describes four different variations of it. A simple definition however would be:

When a single (slow) object prevents other/following objects from making progress

A good real-life metaphor is a grocery store with just a single check-out counter. One customer buying a lot of items can end up delaying everyone behind them, as customers are served in a First In, First Out manner. Another example is a highway with just a single lane. One car crash on this road can end up jamming the entire passage for a long time. As such, even a single issue at the “head” can “block” the entire “line”.

This concept has been one of the hardest Web performance problems to solve. To understand this, let’s start at its incarnation in our trusted workhorse: HTTP version 1.1

HOL blocking in HTTP/1.1

HTTP/1.1 is a protocol from a simpler time. A time when protocols could still be text-based and readable on the wire. This is illustrated in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1: server HTTP/1.1 response for script.js

In this case, the browser requested the simple script.js file (green) over HTTP/1.1, and Figure 1 shows the server’s response to that request. We can see that the HTTP aspect itself is straightforward: it just adds some textual “headers” (red) directly in front of the plaintext file content or “payload”. Headers + payload are then passed down to the underlying TCP (orange) for actual transport to the client. For this example, let’s pretend we cannot fit the entire file into 1 TCP packet and it has to be split up into two parts.

Note: in reality, when using HTTPS, there is another Security layer in between HTTP and TCP, where the TLS protocol is typically used. However, we omit that here for clarity. I did include a bonus section at the end that details a TLS-specific HOL blocking variant and how QUIC prevents it. Feel free to read it (and the other bonus sections) after reading the main text.

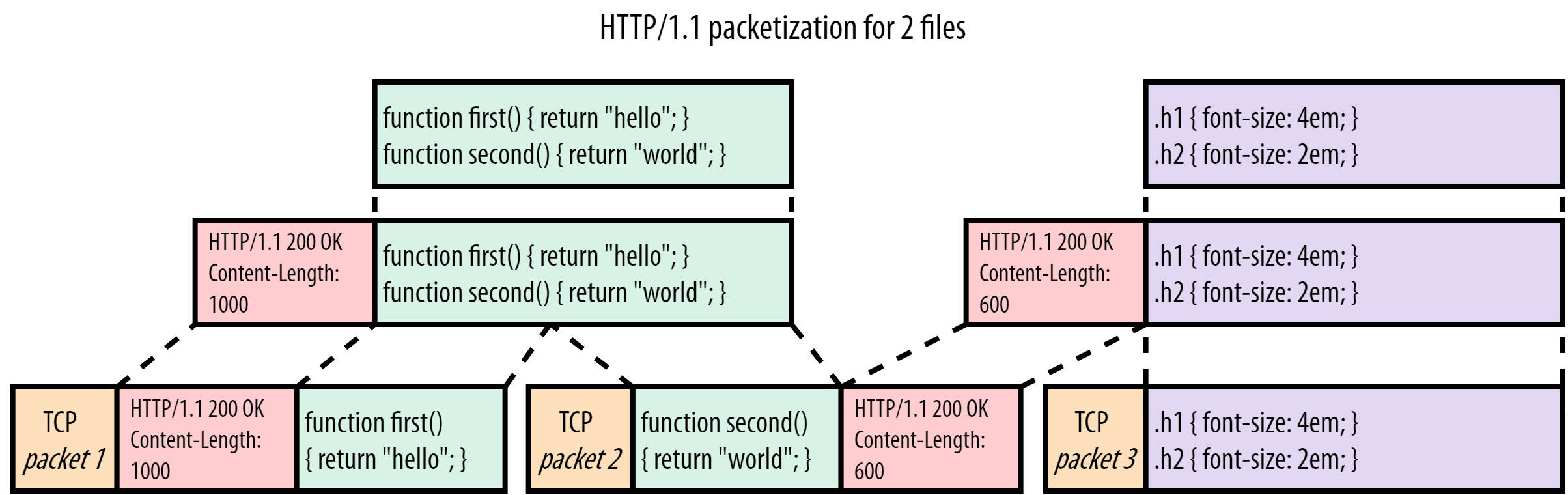

Now let’s see what happens when the browser also requests style.css in Figure 2:

Figure 2: server HTTP/1.1 response for script.js and style.css

In this case, we are sending style.css (purple) after the response for script.js has been transmitted. The headers and content for style.css are simply appended after the JavaScript (JS) file. The receiver uses the Content-Length header to know where each response ends and another starts (in our simplified example, script.js is 1000 bytes large, while style.css is just 600 bytes).

All of that seems sensible enough in this simple example with two small files. However, imagine a scenario in which the JS file is much larger than CSS (say 1MB instead of 1KB). In this case, the CSS would have to wait before the entire JS file was downloaded, even though it is much smaller and thus could be parsed/used earlier. Visualizing this more directly, using the number 1 for large_script.js and 2 for style.css, we would get something like this:

11111111111111111111111111111111111111122

You can see this is an instance of the Head-of-Line blocking problem! Now you might think: that’s easy to solve! Just have the browser request the CSS file before the JS file! Crucially however, the browser has no way of knowing up-front which of the two will end up being the larger file at request time. This is because there is no way to for instance indicate in the HTML how large a file is (something like this would be lovely, HTML working group: <img src="thisisfine.jpg" size="15000" />).

The “real” solution to this problem would be to employ multiplexing. If we can cut up each file’s payload into smaller pieces or “chunks”, we can mix or “interleave” those chunks on the wire: send a chunk for the JS, one for the CSS, then another for the JS again, etc. until the files are downloaded. With this approach, the smaller CSS file will be downloaded (and usable) much earlier, while only delaying the larger JS file by a bit. Visualized with numbers we would get:

12121111111111111111111111111111111111111

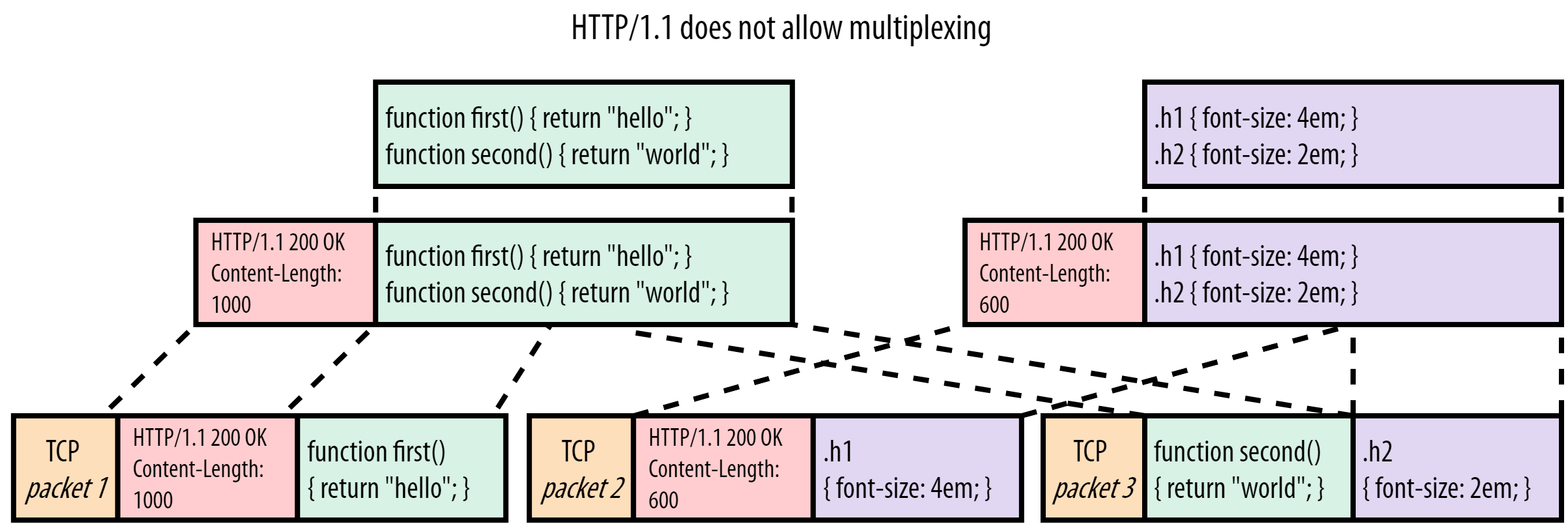

Sadly however, this multiplexing is not possible in HTTP/1.1 due to some fundamental limitations with the protocol’s assumptions. To understand this, we don’t even need to keep looking at the large-vs-small resource scenario, as it already shows up in our example with the two smaller files. Consider Figure 3, where we interleave just 4 chunks for the two resources:

Figure 3: server HTTP/1.1 multiplexing for script.js and style.css

The main problem here is that HTTP/1.1 is a purely textual protocol that only appends headers to the front of the payload. It does nothing further to differentiate individual (chunks of) resources from one another. Let’s illustrate this with an example of what would happen if we tried it anyway. In Figure 3, the browser starts parsing the headers for script.js and expects 1000 bytes of payload to follow (the Content-Length). It however only receives 450 JS bytes (the first chunk) and then starts reading the headers for style.css. It ends up interpreting the CSS headers and the first CSS chunk as part of the JS, as the payloads and headers for both files are just plaintext. Making matters worse, it stops after reading 1000 bytes, ending up somewhere halfway through the second script.js chunk. At this point, it doesn’t see valid new headers and has to drop the rest of TCP packet 3. The browser then passes what it thinks is script.js to the JS parser, which fails because it’s not valid JavaScript:

function first() { return "hello"; }

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Length: 600

.h1 { font-size: 4em; }

func

Again, you could say there’s an easy solution: have the browser look for the HTTP/1.1 {statusCode} {statusString}\n pattern to see when a new header block starts. That might work for TCP packet 2, but will fail in packet 3: how would the browser know where the green script.js chunk ends and the purple style.css chunk begins?

This is a fundamental limitation of the way the HTTP/1.1 protocol was designed. If you have a single HTTP/1.1 connection, resource responses always have to be delivered in-full before you can switch to sending a new resource. This can lead to severe HOL blocking issues if earlier resources are slow to create (for example a dynamically generated index.html that is filled from database queries) or, as above, if earlier resources are large.

This is why browsers started opening multiple parallel TCP connections (typically 6) for each page load over HTTP/1.1. That way, requests can be distributed across those individual connections and there is no more HOL blocking. That is, unless you have more than 6 resources per page… which is of course quite common. This is where the practice of “sharding” your resources over multiple domains (img.mysite.com, static.mysite.com, etc.) and Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) comes from. As each individual domain gets 6 connections, browsers will open up to 30-ish TCP connections in total for each page load. This works, but has considerable overhead: setting up a new TCP connection can be expensive (for example in terms of state and memory at the server, as well as calculations to setup TLS encryption) and takes some time (especially for an HTTPS connection, as TLS requires its own handshake).

As this problem cannot be solved with HTTP/1.1 and the patchwork solution of parallel TCP connections didn’t scale too well over time, it was clear a totally new approach was needed, which is what became HTTP/2.

Note: the old guard reading this might wonder about HTTP/1.1 pipelining. I decided not to discuss that here to keep the overall story flowing, but people interested in even more technical depth can read the bonus section at the end.

HOL blocking in HTTP/2 over TCP

So, let’s recap. HTTP/1.1 has a HOL blocking problem where a large or slow response can delay other responses behind it. This is mainly because the protocol is purely textual in nature and doesn’t use delimiters between resource chunks. As a workaround, browsers open many parallel TCP connections, which is not efficient and doesn’t scale.

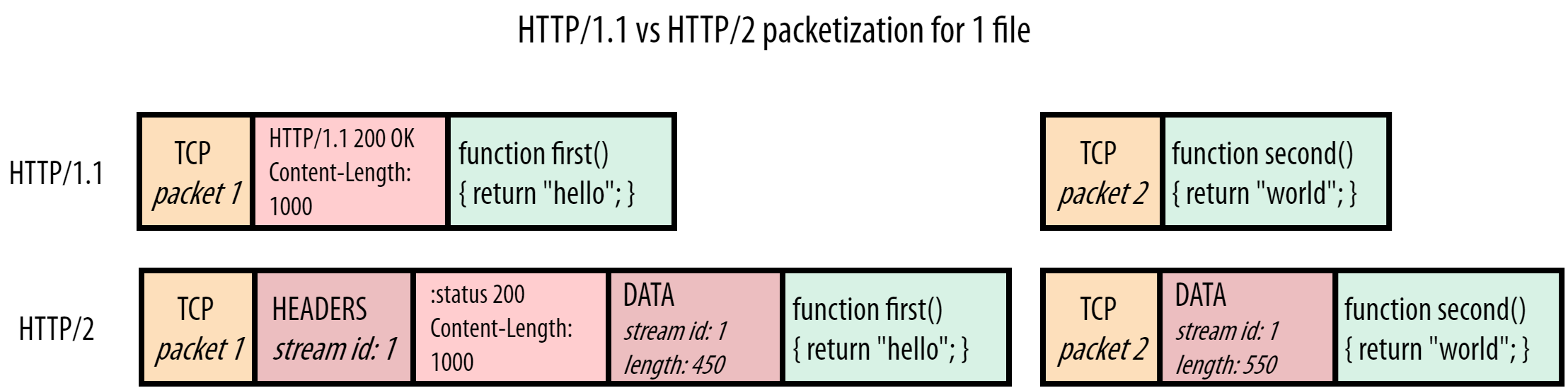

As such, the goal for HTTP/2 was quite clear: make it so that we can move back to a single TCP connection by solving the HOL blocking problem. Stated differently: we want to enable proper multiplexing of resource chunks. This wasn’t possible in HTTP/1.1 because there was no way to discern to which resource a chunk belongs, or where it ends and another begins. HTTP/2 solves this quite elegantly by prepending small control messages, called frames, before the resource chunks. This can be seen in Figure 4:

Figure 4: server HTTP/1.1 vs HTTP/2 response for script.js

HTTP/2 puts a so-called DATA frame in front of each chunk. These DATA frames mainly contain two critical pieces of metadata. First: which resource the following chunk belongs to. Each resource’s “bytestream” is assigned a unique number, the stream id. Second: how large the following chunk is. The protocol has many other frame types as well, of which Figure 5 also shows the HEADERS frame. This again uses the stream id to indicate which response these headers belong to, so that headers can even be split up from their actual response data.

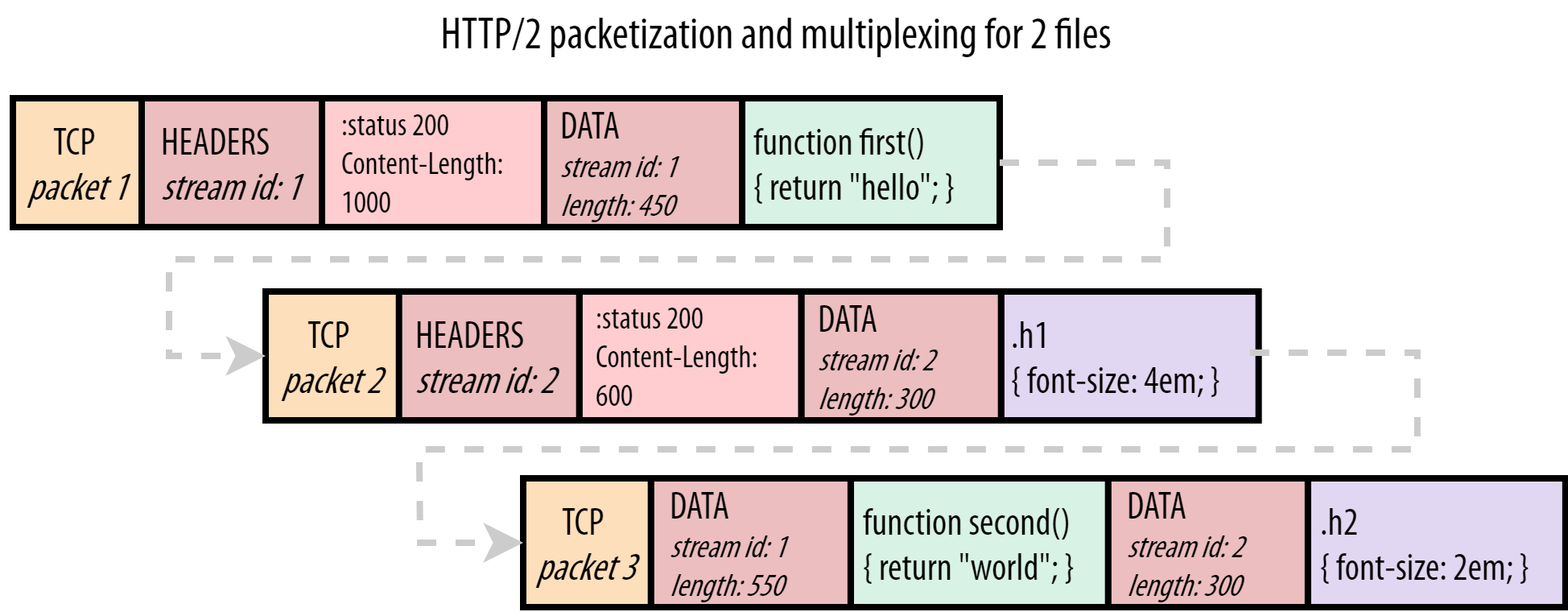

Using these frames, it follows that HTTP/2 indeed allows proper multiplexing of several resources on one connection, see Figure 5:

Figure 5: multiplexed server HTTP/2 responses for script.js and style.css

Unlike our example for Figure 3, the browser can now perfectly deal with this situation. It first processes the HEADERS frame for script.js and then the DATA frame for the first JS chunk. From the chunk length included in the DATA frame, the browser knows it only extends to the end of TCP packet 1, and that it needs to look for a completely new frame starting in TCP packet 2. There it indeed finds the HEADERS for style.css. The next DATA frame has a different stream id (2) than the first DATA frame (1), so the browser knows this belongs to a different resource. The same happens for TCP packet 3, where the DATA frame stream ids are used to “de-multiplex” the response chunks to their correct resource “streams”.

By “framing” individual messages HTTP/2 is thus much more flexible than HTTP/1.1. It allows for many resources to be sent multiplexed on a single TCP connection by interleaving their chunks. It also solves HOL blocking in the case of a slow first resource: instead of waiting for the database-backed index.html to be generated, the server can simply start sending data for other resources while it waits for index.html.

An important consequence of HTTP/2’s approach is that we suddenly also need a way for the browser to communicate to the server how it would like the single connection’s bandwidth to be distributed across resources. Put differently: how resource chunks should be “scheduled” or interleaved. If we again visualize this with 1’s and 2’s, we see that for HTTP/1.1, the only option was 11112222 (let’s call that sequential). HTTP/2 however has a lot more freedom:

- Fair multiplexing (for example two progressive JPEGs): 12121212

- Weighted multiplexing (2 is twice as important as 1): 221221221

- Reversed sequential scheduling (for example 2 is a key Server Pushed resource): 22221111

- Partial scheduling (stream 1 is aborted and not sent in full): 112222

Which of these is used is driven by the so-called “prioritization” system in HTTP/2 and the chosen approach can have a big impact on Web performance. That is however a very complex topic by itself and you don’t really need to understand it for the rest of this blogpost, so I’ve left it out here (though I do have an extensive lecture on this on YouTube).

I think you’ll agree that, with HTTP/2’s frames and its prioritization setup, it indeed solves HTTP/1.1’s HOL blocking problem. This means my work here is done and we can all go home. Right? Well, not so fast there bucko. We’ve solved HTTP/1.1 HOL blocking, yes, but what about TCP HOL blocking?

TCP HOL blocking

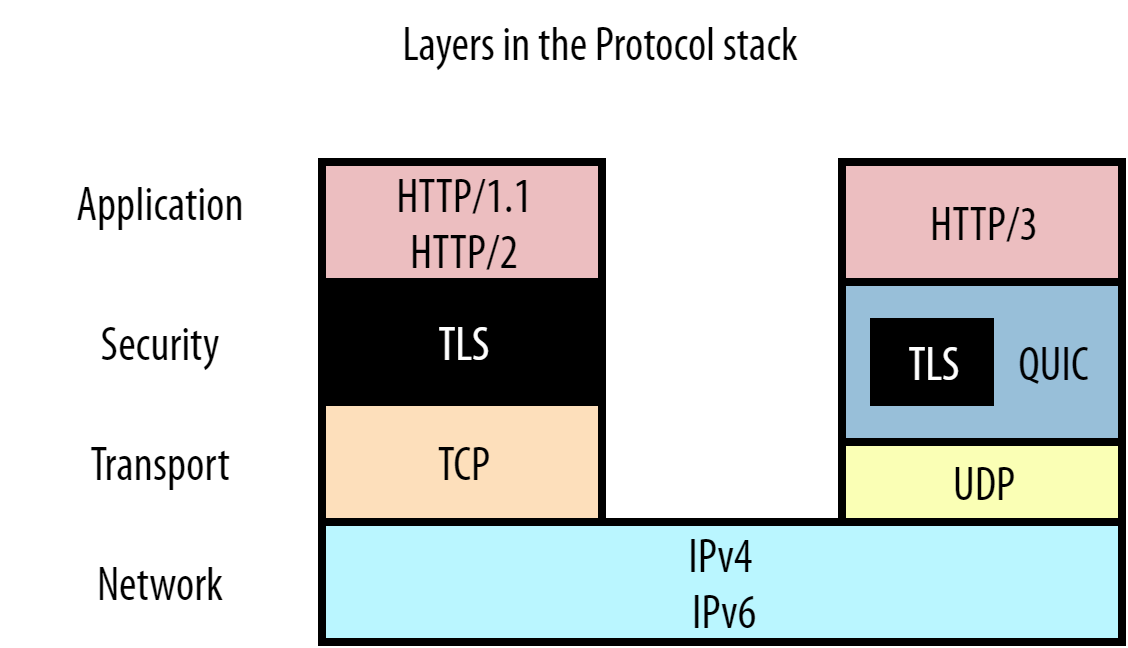

As it turns out, HTTP/2 only solved HOL blocking at the HTTP level, what we might call “Application Layer” HOL blocking. There are however other layers below that to consider in the typical networking model. You can see this clearly in Figure 6:

Figure 6: the top few protocol layers in the typical networking model.

HTTP is at the top, but is supported first by TLS at the Security Layer (see the Bonus TLS section), which in turn is carried by TCP at the Transport layer. Each of these protocols wrap the data from the layer above it with some metadata. For example the TCP packet header is prepended to our HTTP(S) data, which then gets put inside an IP packet etc. This allows for a relatively neat separation between the protocols. This in turn is good for their re-usability: a Transport Layer protocol like TCP doesn’t have to care about what type of data it is transporting (it could be HTTP, it could be FTP, it could be SSH, who knows), and IP works fine for both TCP and UDP.

This does however have important consequences if we want to multiplex multiple HTTP/2 resources onto one TCP connection. Consider Figure 7:

![]()

Figure 7: difference in perspective between HTTP/2 and TCP

While both we and the browser understand we are fetching JavaScript and CSS files, even HTTP/2 doesn’t (need to) know that. All it knows is that it is working with chunks from different resource stream ids. However, TCP doesn’t even know that it’s transporting HTTP! All TCP knows is that it has been given a series of bytes that it has to get from one computer to another. For this it uses packets of a certain maximum size, typically around 1450 bytes. Each packet just tracks which part of the data (byte range) it carries so the original data can be reconstructed in the correct order.

Put differently, there is a mismatch in perspective between the two Layers: HTTP/2 sees multiple, independent resource bytestreams, but TCP sees just a single, opaque bytestream. An example is Figure 7’s TCP packet 3: TCP just knows it is carrying byte 750 to byte 1599 of whatever it is transporting. HTTP/2 on the other hand knows there are actually two chunks of two separate resources in packet 3. (Note: In reality, each HTTP/2 frame (like DATA and HEADERS) is also a couple of bytes in size. For simplicity, I haven’t counted that extra overhead or the HEADERS frames here to make the numbers more intuitive.)

All of this might seem like unnecessary details, until you realize that the Internet is a fundamentally unreliable network. Packets can and do get lost and delayed during transport from one endpoint to the other. This is exactly one of the reasons why TCP is so popular: it ensures reliability on top of the unreliable IP. It does this quite simply by retransmitting copies of lost packets.

We can now understand how that can lead to HOL blocking at the Transport Layer. Consider again Figure 7 and ask yourself: what should happen if TCP packet 2 is lost in the network, but somehow packet 1 and packet 3 do arrive? Remember that TCP doesn’t know it’s carrying HTTP/2, just that it needs to deliver data in-order. As such, it knows the contents of packet 1 are safe to use and passes those to the browser. However, it sees that there is a gap between the bytes in packet 1 and those in packet 3 (where packet 2 fits), and thus cannot yet pass packet 3 to the browser. TCP keeps packet 3 in its receive buffer until it receives the retransmitted copy of packet 2 (which takes at least 1 round-trip to the server), after which it can pass both to the browser in the correct order. Put differently: the lost packet 2 is HOL blocking packet 3!

It might not be clear why this is a problem though, so let’s dig deeper by looking at what is actually inside the TCP packets at the HTTP layer in Figure 7. We can see that TCP packet 2 carries only data for stream id 2 (the CSS file) and that packet 3 carries data for both streams 1 (the JS file) and 2. At the HTTP level, we know those two streams are independent and clearly delineated by the DATA frames. As such, we could in theory perfectly pass packet 3 to the browser without waiting for packet 2 to arrive. The browser would see a DATA frame for stream id 1 and would be able to directly use it. Only stream 2 would have to be put on hold, waiting for packet 2’s retransmit. This would be more efficient than what we get from TCPs approach, which ends up blocking both stream 1 and 2.

Another example is the situation where packet 1 is lost, but 2 and 3 are received. TCP will again hold back both packets 2 and 3, waiting for 1. However, we can see that at the HTTP/2 level, the data for stream 2 (the CSS file) is present completely in packets 2 and 3 and doesn’t have to wait for packet 1’s retransmit. The browser could have perfectly parsed/processed/used the CSS file, but is stuck waiting for the JS file’s retransmit.

In conclusion, the fact that TCP does not know about HTTP/2’s independent streams means that TCP-Layer HOL blocking (due to lost or delayed packets) also ends up HOL blocking HTTP!

Now, you might ask yourself: then what was the point? Why do HTTP/2 at all if we still have TCP HOL blocking? Well, the main reason is that while packet loss does happen on networks, it is still relatively rare. Especially on high-speed, cabled networks, packet loss rates are on the order of 0.01%. Even on the worst cellular networks, you will rarely see rates higher than 2% in practice. This is combined with the fact that packet loss and also jitter (delay variations in the network), are often bursty. A packet loss rate of 2% does not mean that you will always have 2 packets out of every 100 being lost (for example packet nr 42 and nr 96). In practice, it would probably be more like 10 consecutive packets being lost in a total of 500 (say packet nr 255 to 265). This is because packet loss is often caused by temporarily overflowing memory buffers in routers in the network path, which start dropping packets they cannot store. Again though, the details aren’t important here (but available elsewhere if you’d like to know more). What is important is that: yes, TCP HOL blocking is real, but it has a much smaller impact on Web performance than HTTP/1.1 HOL blocking, which you are almost guaranteed to hit every time and which also suffers from TCP HOL blocking!

However, this is mainly true when comparing HTTP/2 on a single connection with HTTP/1.1 on a single connection. As we’ve seen before, that’s not really how it works in practice, as HTTP/1.1 typically opens multiple connections. This allows HTTP/1.1 to somewhat mitigate not only the HTTP-level but also the TCP-level HOL blocking. As such, in some cases, HTTP/2 on a single connection has a hard time being faster than or even as fast as HTTP/1.1 on 6 connections. This is mainly due to TCP’s “congestion control” mechanism. This is however yet another very deep topic that is not core to our HOL blocking discussion, so I have moved it to another Bonus section at the end for those interested.

All in all, in practice, we see that (perhaps unexpectedly), HTTP/2 as it is currently deployed in browsers and servers is typically as fast or slightly faster than HTTP/1.1 in most conditions. This is in my opinion partly because websites got better at optimizing for HTTP/2, and partly because browsers often still open multiple parallel HTTP/2 connections (either because sites still shard their resources over different servers, or because of security-related side-effects), thus getting the best of both worlds.

However, there are also some cases (especially on slower networks with higher packet loss) where HTTP/1.1 on 6 connections will still outshine HTTP/2 on one connection, which is often due to the TCP-level HOL blocking problem. It is this fact that was a large motivator for the development of the new QUIC transport protocol as a replacement for TCP.

HOL blocking in HTTP/3 over QUIC

After all that, we’re finally ready to start talking about the new stuff! But first, let’s summarize what we’ve learned so far:

- HTTP/1.1 had HOL blocking because it needs to send its responses in full and cannot multiplex them

- HTTP/2 solves that by introducing “frames” that indicate to which “stream” each resource chunk belongs

- TCP however does not know about these individual “streams” and just sees everything as 1 big stream

- If a TCP packet is lost, all later packets need to wait for its retransmission, even if they contain unrelated data from different streams. TCP has Transport Layer HOL blocking.

I’m pretty sure you can by now predict how we can solve TCP’s issues, right? After all, the solution is quite simple: we “just” need to make the Transport Layer aware of the different, independent streams! That way, if data for one stream is lost, the Transport itself knows it does not need to hold back the other streams.

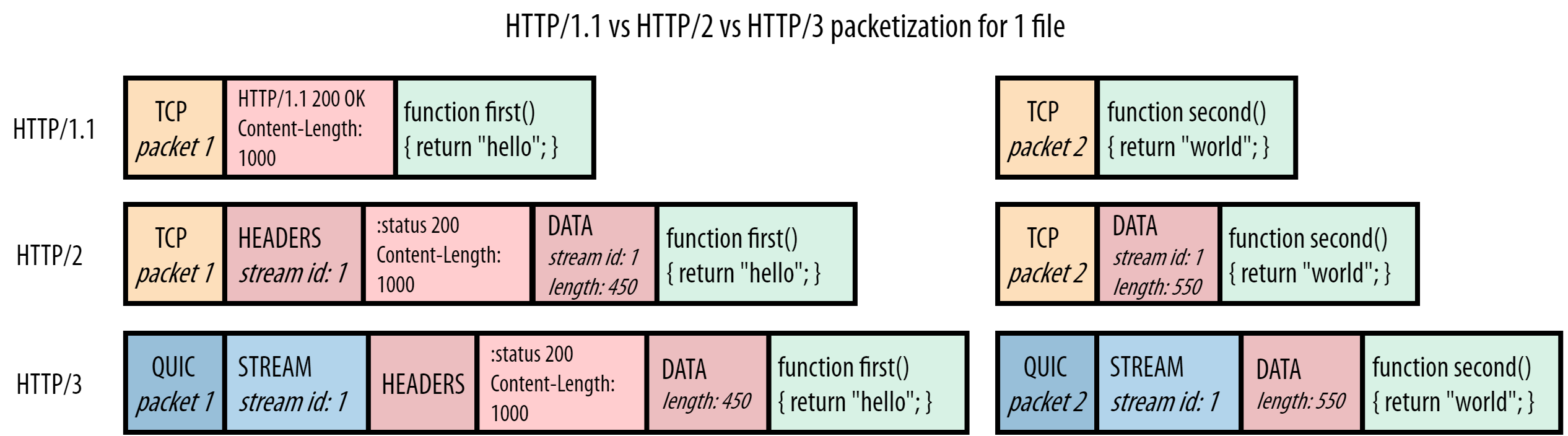

Even though the solution is simple in concept, it has been very difficult to implement in practice. For various reasons, it was impossible to change TCP itself to make it stream-aware. The chosen alternative approach was to implement a completely new Transport Layer protocol in the form of QUIC. To make QUIC practically deployable on the Internet, it runs on top of the unreliable UDP protocol. Yet, very importantly, this does not mean QUIC itself is also unreliable! In many ways, QUIC should be seen as a TCP 2.0. It includes the best versions all of TCP’s features (reliability, Congestion Control, Flow Control, ordering, etc.) and many more besides. QUIC also fully integrates TLS (see Figure 6) and doesn’t allow unencrypted connections. Because QUIC is so different from TCP, it also means we cannot just run HTTP/2 on top of it, which is why HTTP/3 was created (we will talk about this more in a moment). This blogpost will already be long enough without also discussing QUIC in more detail (see other sources for that), so I will instead just focus on the few parts that we need to understand our current HOL blocking discussion. These are shown in Figure 8:

Figure 8: server HTTP/1.1 vs HTTP/2 vs HTTP/3 response for script.js

We observe that making QUIC aware of the different streams was pretty straightforward. QUIC was inspired by HTTP/2’s framing-approach and also adds its own frames; in this case the STREAM frame. The stream id, which was previously in HTTP/2’s DATA frame, is now moved down to the Transport Layer in QUIC’s STREAM frame. This also shows one of the reasons why we needed a new version of HTTP if we want to use QUIC: if we would just run HTTP/2 on top of QUIC, we would have two (potentially conflicting) “stream layers”. HTTP/3 instead removes the stream concept from the HTTP layer (its DATA frames have no stream id) and re-uses the underlying QUIC streams instead.

Note: this doesn’t mean QUIC suddenly knows about JS or CSS files or even that it is transporting HTTP; like TCP, QUIC is supposed to be a generic, re-usable protocol. It just knows that there are independent streams that it can handle individually, without having to know what exactly is in them.

Now that we know about QUIC’s STREAM frames, it’s also easy to see how they help solve Transport Layer HOL blocking in Figure 9:

![]()

Figure 9: difference in perspective between TCP and QUIC

Much like HTTP/2’s DATA frames, QUIC’s STREAM frames track the byte ranges for each stream individually. This in contrast to TCP, which just appends all stream data in one big blob. Like before, let’s consider what would happen if QUIC packet 2 is lost but 1 and 3 arrive. Similar to TCP, the data for stream 1 in packet 1 can just be passed to the browser. However, for packet 3, QUIC can be smarter than TCP. It looks at the byte ranges for stream 1 and sees that this STREAM frame perfectly follows the first STREAM frame for stream id 1 (byte 450 follows byte 449, so there are no byte gaps in the data). It can immediately give that data to the browser for processing as well. For stream id 2 however, QUIC does see a gap (it hasn’t received bytes 0-299 yet, those were in the lost QUIC packet 2). It will hold on to that STREAM frame until the retransmission of QUIC packet 2 arrives. Contrast this again to TCP, which also held back stream 1’s data in packet 3!

Something similar happens in the other situation where packet 1 is lost but 2 and 3 arrive. QUIC knows it has received all expected data for stream 2 and just passed that along to the browser, only holding up stream 1. We can see that for this example, indeed, QUIC solves TCP’s HOL blocking!

This approach has a couple of important consequences though. The most impactful one is that QUIC data might no longer be delivered to the browser in exactly the same order as it was sent. For TCP, if you send packets 1, 2 and 3, their contents will be delivered in exactly that order to the browser (that’s what’s causing the HOL blocking in the first place). For QUIC though, in the second example above where packet 1 is lost, the browser instead first sees the contents of packet 2, then the last part of packet 3, then (the retransmission of) packet 1 and then the first part of packet 3. Put differently: QUIC retains ordering within a single resource stream but no longer across individual streams.

This is the second and arguably most important reason for needing HTTP/3, as it turns out that several systems in HTTP/2 rely -very- heavily on TCP’s fully deterministic ordering across streams. For example, HTTP/2’s prioritization system works by transmitting operations that change the layout of a tree data structure (for example, add resource 5 as a child of resource 6). If those operations are applied in a different order than they were sent (which would now be possible over QUIC), the client and the server could end up with different prioritization state. Something similar happens for HTTP/2’s header compression system HPACK. It’s not important to understand the specifics here, just the conclusion: it turns out to be exceptionally difficult to adapt these HTTP/2 systems to QUIC directly. As such, for HTTP/3, some systems use radically different approaches. For example, QPACK is HTTP/3’s version of HPACK and allows a self-chosen trade-off between potential HOL blocking and compression performance. HTTP/2’s prioritization system is even completely removed and will probably be replaced with a much simplified version for HTTP/3. All of this because, unlike TCP, QUIC does not fully guarantee that data which is sent first is also received first.

So, all that work on QUIC and a re-imagined HTTP version just to remove Transport Layer HOL blocking. I sure hope that was worth it…

Do QUIC and HTTP/3 really completely remove HOL blocking?

If you’ll allow me a bit of bad form, I’d like to quote myself from a few paragraphs ago:

QUIC retains ordering within a single resource stream

That’s pretty logical when you think about it. It basically says: if you have a JavaScript file, that file needs to be re-assembled exactly as it was created by the developer (or, let’s be honest, by webpack), or the code won’t work. The same goes for any type of file: putting an image back together in a random order would mean some pretty weird digital Christmas cards from your aunt (even weirder ones). This means that we still have a form of HOL blocking, even in QUIC: if there is a byte gap inside a single stream, the latter parts of the stream are still stuck waiting until that gap is filled.

This has a crucial implication: QUIC’s HOL blocking removal only works if there are multiple resource streams active at the same time. That way, if there is packet loss on one of the streams, the others can still make progress. That’s what we’ve seen in the examples from Figure 9 above. However, if there is only a single stream active at a given moment, any loss will impact that lonely stream and we will still be HOL blocked, even in QUIC. So, the real question is: how often are we in the situation of having multiple simultaneous streams?

As explained for HTTP/2, this is something that can be configured by using an appropriate resource scheduler/multiplexing approach. Streams 1 and 2 can be sent 1122, 2121, 1221, etc. and the browser can specify the scheme it would like the server to follow using the prioritization system (this is still true for HTTP/3). So the browser could say: Hey! I’m noticing heavy packet loss on this connection. I’m going to have the server send me the resources in a 121212 pattern instead of 111222. That way, if a single packet for 1 is lost, 2 can still make progress. The problem with this however, is that the 121212 pattern (or similar) is often not optimal for resource loading performance.

This is yet another complex topic that I don’t want to get too deep into right now (I do have an extensive talk on this on YouTube for those interested). However, the basic concept is easy enough to understand with our simple example of the JS and CSS files. As you probably know, a browser needs to receive -the entire- JS or CSS file before it can actually execute/apply it (while some browsers can already start compiling/parsing partially downloaded files, they still need to wait for them to complete before actually using them). Heavily multiplexing resource chunks for those files however will end up delaying them both:

With multiplexing (slower):

---------------------------

Stream 1 is only ready to be used here

â–¼

12121212121212121212121212121212

â–²

Stream 2 is done downloading here

Without multiplexing/sequential (faster for stream 1):

------------------------------------------------------

Stream 1 is done downloading here and can be used much earlier

â–¼

11111111111111111122222222222222

â–²

Stream 2 is still done here

Now, there is a lot of nuance to this topic, and there are certainly situations where the multiplexing approach is faster (for example if one of the files is much smaller than the other one, as discussed early in this post). However, in general for most pages and most resource types, we could say the sequential approach works best (again, see the YouTube link above for too much information on this).

Now, what does this mean? It means we have two conflicting recommendations for optimal performance:

- To profit from QUIC’s HOL blocking removal: send resources multiplexed (12121212)

- To make sure browsers can process core resources ASAP: send resources sequentially (11112222)

So which of these is correct? Or at least: which of these should take precedence over the other? Sadly, that’s not something I can give you a definitive answer on at this time, as it is a topic of my ongoing research. The main reason why this is difficult is because packet loss patterns are difficult to predict.

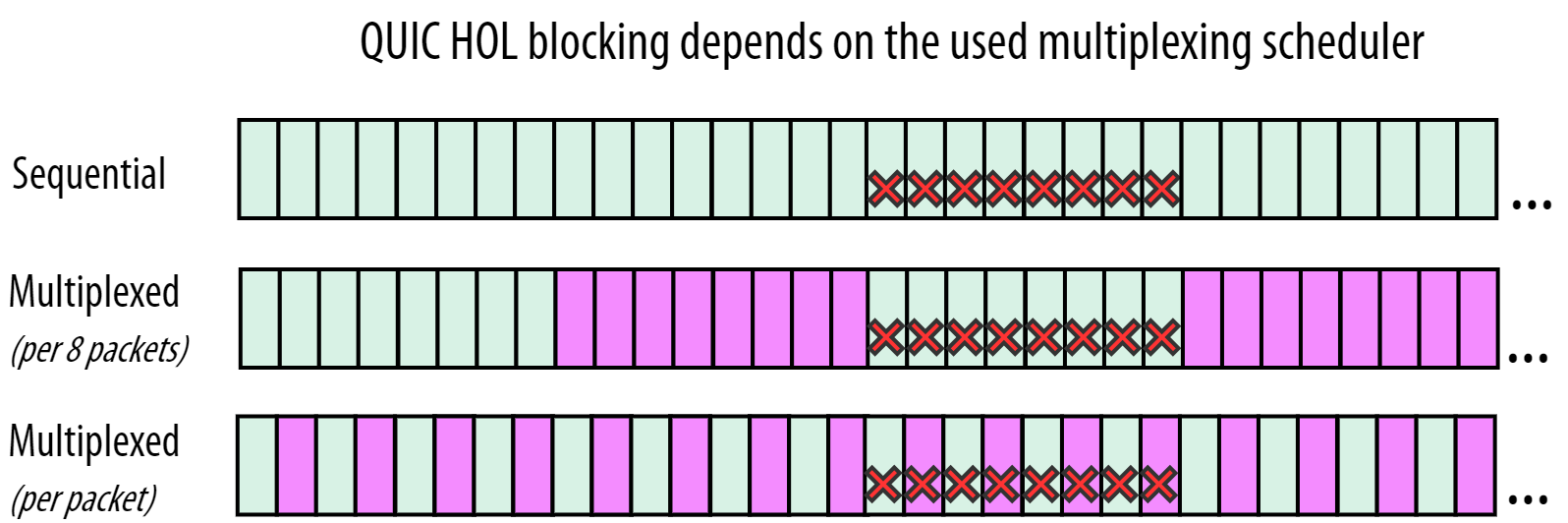

As we’ve discussed above, packet loss is often bursty and grouped. This means that our example above of 12121212 is already too simplified. Figure 10 gives an overview that’s a little bit more realistic. Here, we assume we have a single burst of 8 lost packets while we are downloading 2 streams (green and purple):

Figure 10: impact of stream multiplexing on HOL blocking prevention in HTTP/3 over QUIC. Each rectangle is a separate QUIC packet carrying data for one stream. The red crosses indicate the lost packets.

In the top row of Figure 10, we see the sequential case that is (usually) better for resource loading performance. Here, we see that QUIC’s HOL blocking removal indeed doesn’t really help all that much: the received green packets after the loss cannot be processed by the browser as they belong to the same stream that experienced the loss. The data for the second (purple) stream hasn’t been received yet, so it cannot be processed.

This is different from the middle row, where (by chance!) the 8 lost packets are all from the green stream. This means that the received purple packets at the end now -can- be processed by the browser. However, as discussed before, the browser probably won’t benefit from that all too much if it’s a JS or CSS file, if there is more purple data coming. So here, we profit somewhat from QUIC’s HOL blocking removal (as purple isn’t blocked by green), but at the possible expense of overall resource loading performance (as multiplexing causes files to complete later).

The bottom row is pretty much the worst case. The 8 lost packets are distributed across the two streams. This means that both streams are now HOL blocked: not because they’re waiting on each other, as would be the case with TCP, but because each stream still needs to be ordered by itself.

Note: this is also why most QUIC implementations very rarely create packets containing data from more than 1 stream at the same time. If one of those packets is lost, it immediately leads to HOL blocking for all streams in the single packet!

So, we see that there is potentially some kind of a sweet spot (the middle row) where the trade-off between HOL blocking prevention and resource loading performance might be worth it. However, as we said, the loss pattern is difficult to predict. It won’t always be 8 packets. They won’t always be the same 8 packets. If we get it wrong and the lost packets are shifted just one to the left, we suddenly also have 1 purple packet missing, which basically demotes us down to something similar to the bottom row…

I think you will agree with me that that sounds quite complex to get working, probably even too complex. And even then, the question is how much it would help. As discussed before, packet loss is typically relatively rare on many network types, possibly (probably?) too rare to see much of an impact from QUIC’s HOL blocking removal. On the other end, it has been well documented that multiplexing resources packet-per-packet (bottom row of Figure 10) is quite bad for resource loading performance, no matter if you’re using HTTP/2 or HTTP/3.

As such, one might say that while QUIC and HTTP/3 no longer suffer from Application or Transport Layer HOL blocking, this might not matter all that much in practice. I can’t say this for sure, because we don’t have fully finished QUIC and HTTP/3 implementations yet, so I don’t have final measurements to go on. However, my personal gut feeling (which -is- backed by my results from several early experiments) says that QUIC’s HOL blocking removal probably won’t actually help all that much for Web performance, as ideally you don’t want many streams being multiplexed anyway for resource loading performance. And, if you do want it to work well, you’d have to very smartly tweak your multiplexing approach to the type of connection, as you definitely don’t want to be multiplexing heavily on fast networks with very low packet loss (as they won’t suffer much HOL blocking anyway). Personally, I don’t see that happening.

Note: here, at the end, you might have noticed a bit of an inconsistency in my story. At the start, I said the problem with HTTP/1.1 is that it doesn’t allow multiplexing. At the end, I say multiplexing isn’t that important in practice anyway. To help resolve this apparent contradiction, I’ve added another Bonus section

Summary and Conclusion

In this (long, I know) post, we have tracked HOL blocking through time. We first discussed why HTTP/1.1 suffers from Application Layer HOL blocking. This is mainly because HTTP/1.1 does not have a way to identify chunks of individual resources. HTTP/2 uses frames to mark those chunks and enables multiplexing. This solves HTTP/1.1’s problem, but HTTP/2 is sadly still limited by the underlying TCP. Because TCP abstracts the HTTP/2 data as a single, ordered, but opaque stream, it will suffer a form of HOL blocking if packets are lost or severely delayed on the network. QUIC solves this by bringing some of HTTP/2’s concepts down into the Transport layer. This in turn has severe repercussions, as data across streams is no longer fully ordered. This eventually led to the need for an the entirely new version 3 of HTTP, which only runs on top of QUIC (while HTTP/2 only runs on top of TCP, see also Figure 6).

We needed all that context to think critically about how much the HOL blocking removal in QUIC (and thus HTTP/3) will actually help for Web performance in practice. We saw that it would probably only have a large impact on networks with a lot of packet loss. We also discussed why, even then, you would need to multiplex resources and get lucky with how loss impacts that multiplexing. We saw why that might actually do more harm than good, as resource multiplexing is typically not the best idea for Web performance overall. We concluded that, while it’s a bit early to tell for sure, QUIC and HTTP/3’s HOL blocking removal probably won’t do all that much for Web performance in the majority of the cases.

So… where does that leave us Web performance afficionados? Ignore QUIC and HTTP/3 and stick with HTTP/2 + TCP? I sure hope not! I still believe HTTP/3 will be faster than HTTP/2 overall, as QUIC also includes other performance improvements. It for example has less overhead on the wire than TCP, is much more flexible in terms of Congestion Control and, most importantly, has the 0-RTT connection establishment feature. I feel that especially 0-RTT will provide the most Web performance benefits, though there are plenty of challenges there as well. I will write another blogpost on 0-RTT in the future, but if you can’t wait to know more about amplification prevention, replay attacks, initial congestion window size, etc. watch another of my YouTube lectures or read my recent paper.

If you liked all that and want more in the future, please give me a follow on twitter @programmingart.

A “living document” version of this post can be found on github. Let me know if you have tips on how to improve it!

Thank you for reading!

Bonus: HTTP/1.1 pipelining

HTTP/1.1 includes a feature called “pipelining” which is in my opinion often misunderstood. I’ve seen many posts and even books where people claim that HTTP/1.1 pipelining solves the HOL blocking issue. I’ve even seen some people saying that pipelining is the same as proper multiplexing. Both statements are false.

I find it easiest to explain HTTP/1.1 pipelining with an illustration like the one in Bonus Figure 1:

Bonus Figure 1: HTTP/1.1 pipelining

Without pipelining (left side of Bonus Figure 1), the browser has to wait to send the second resource request until the response for the first request has been completely received (again using Content-Length). This adds one Round-Trip-Time (RTT) of delay for each request, which is bad for Web performance.

With pipelining then (middle of Bonus Figure 1), the browser does not have to wait for any response data and can now send the requests back-to-back. This way we save some RTTs during the connection, making the loading process faster. As a side-note, look back at Figure 2: you see that pipelining is actually used there as well, as the server bundles data from the script.js and style.css responses in TCP packet 2. This is of course only possible if the server received both requests around the same time.

Crucially however, this pipelining only applies to the requests from the browser. As the [HTTP/1.1 specification][h1spec] says:

A server MUST send its responses to those [pipelined] requests in the same order that the requests were received.

As such, we see that actual multiplexing of response chunks (illustrated on the right side of Bonus Figure 1) is still not possible with HTTP/1.1 pipelining. Put differently: pipelining solves HOL blocking for requests, but not for responses. Sadly, it’s arguably the response HOL blocking that causes the most issues for Web performance.

To make matters worse, most browsers actually do not use HTTP/1.1 pipelining in practice because it can make HOL blocking more unpredictable in the setup with multiple parallel TCP connections. To understand this, let’s imagine a setup where three files A (large), B (small) and C (small) are being requested from the server over two TCP connections. A and B are each requested on a different connection. Now, on which connection should the browser pipeline the request for C? As we said before, it doesn’t know up-front whether A or B will turn out to be the largest/slowest resource.

If it guesses correctly (B), it can download both B and C in the time it takes to transfer A, resulting in a nice speedup. However, if the guess is wrong (A), the connection for B will be idle for a long time, while C is HOL blocked behind A. This is because HTTP/1.1 also does not provide a way to “abort” a request once it’s been sent (something which HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 do allow). The browser can thus not simply request C over B’s connection once it becomes clear that is going to be the faster one, as it would end up requesting C twice.

To get around all this, modern browsers do not employ pipelining and will even actively delay requests of certain discovered resources (for example images) for a little while to see if more important files (say JS and CSS) are found, to make sure the high priority resources are not HOL blocked.

It is clear that the failure of HTTP/1.1 pipelining was another motivation for HTTP/2’s radically different approach. Yet, as HTTP/2’s prioritization system to steer multiplexing often fails to perform in practice, some browsers have even taken to delaying HTTP/2 resource requests as well to get optimal performance.

Bonus: TLS HOL blocking

As we have said above, the TLS protocol provides encryption (and other things) for Application Layer protocols, such as HTTP. It does this by wrapping the data it gets from HTTP into TLS records, which are conceptually similar to HTTP/2 frames or TCP packets. They for example include a bit of metadata at the start to indicate how long the record is. This record and its HTTP contents are then encrypted and passed to TCP for transport.

As encryption can be an expensive operation in terms of CPU usage, it is typically a good idea to encrypt a good chunk of data at once, as this is typically more efficient. In practice, TLS can encrypt resources in blocks of up to 16KB, which is enough to fill about 11 typical TCP packets (give or take).

Crucially however, TLS can only decrypt a record in its entirety, which is why a form of TLS HOL blocking can occur. Imagine that the TLS record was spread out over 11 TCP packets, and the last TCP packet is lost. Since the TLS record is incomplete, it cannot be decrypted, and is thus stuck waiting for the retransmission of the last TCP packet. Note that in this specific case there is no TCP HOL blocking: there are no packets after number 11 that are stuck waiting for the retransmit. Put differently, if we had used plain HTTP instead of HTTPS in this example, the HTTP data from the first 10 packets could have already been moved to the browser for processing. However, because we need the entire 11-packet TLS record to be able to decrypt it, we have a new form of HOL blocking.

While this is a highly specific case that probably does not happen very frequently in practice, it was still something taken into account when designing the QUIC protocol. As there the goal was to eliminate HOL blocking in all its forms once and for all (or at least as much as possible), even this edge case had to be removed. This is part of the reason why, while QUIC integrates TLS, it will always encrypt data on a per-packet basis and it does not use TLS records directly. As we’ve seen, this is less efficient and requires more CPU than using larger blocks, and is one of the main reasons why QUIC can still be slower than TCP in current implementations.

Bonus: Transport Congestion Control

Transport Layer protocols like TCP and QUIC include a mechanism called Congestion Control. The congestion controller’s main job is to make sure the network isn’t overloaded by too much data at the same time. If that happens the router buffers start overflowing, causing them to drop packets that don’t fit, and we have packet loss. So, what it typically does is start by sending just a little bit of data (usually about 14KB) to see if that makes it through. If the data arrives, the receiver sends acknowledgements back to the sender. As long as all sent data is being acknowledged, the sender doubles its send rate every RTT until a packet loss event is observed (meaning the network is overloaded (a bit) and it needs to back down (a bit)). This is how a TCP connection “probes” for its available bandwidth.

Note: The description above is just one way to do Congestion Control. Nowadays, other approaches are gaining popularity, main among them the BBR algorithm. Instead of looking directly at packet loss, BBR also heavily takes into account RTT fluctuations to determine if a network is getting overloaded, which means it typically causes fewer packet losses itself by probing bandwidth.

Crucially: the congestion control mechanism works for each TCP (and QUIC) connection independently! This in turn has implications for Web performance at the HTTP layer as well. Firstly, this means that HTTP/2’s single connection initially only sends 14KB. However, HTTP/1.1’s 6 connections each send 14KB in their first flight, which is about 84KB! This will compound over time, as each HTTP/1.1 connection doubles its data use each RTT. Secondly, a connection will only lower its sending rate if there is packet loss. For HTTP/2’s single connection, even a single packet loss means it will slow down (in addition to causing TCP HOL blocking!). However, for HTTP/1.1, a single packet loss on just one of the connections will only slow down that one: the other 5 can just keep sending and growing as normal.

This all makes one thing very clear: HTTP/2’s multiplexing is not the same as HTTP/1.1’s downloading resources at the same time(something which I also still see some people claiming). The available bandwidth of the singular HTTP/2 connection is simply distributed across/shared among the different files, but chunks are still sent sequentially. This is different from HTTP/1.1, where things are sent in a truly parallel fashion.

By now, you might be wondering: how then can HTTP/2 ever be faster than HTTP/1.1? That is a good question, one that I have been asking myself on and off for a long time as well. One obvious answer is in cases where you have -many- more than 6 files. This is how HTTP/2 was marketed back in the day: by splitting an image into tiny squares and loading those over HTTP/1.1 vs HTTP/2. This mainly shows off HTTP/2’s HOL blocking removal. For normal/real websites however, things get a lot more nuanced quickly. It depends on the amount of resources, their size, the used prioritization/multiplexing scheme, the RTT to the server, how much loss there actually is and when it happens, how much other traffic is on the link at the same time, the used congestion controller logic, etc. One example where HTTP/1.1 can lose is on networks with limited available bandwidth: the 6 HTTP/1.1 connections each grow their send rate individually, causing them to overload the network quite quickly, after which they all have to back down and have to find their co-existent bandwidth limit through trial and error (prior to HTTP/2, it was thought that HTTP/1.1’s parallel connections could be a main cause of packet loss on the Internet). The single HTTP/2 connection instead grows more slowly, but it is faster to recover after a packet loss event and finds its optimal bandwidth faster. Another, more detailed example with annotated congestion windows where HTTP/2 is faster can be found in this image (not for the faint of heart).

QUIC and HTTP/3 will see similar challenges, as like HTTP/2, HTTP/3 will use a single underlying QUIC connection. You might then say that a QUIC connection is conceptually a bit like multiple TCP connections, as each QUIC stream can be seen as one TCP connection, because loss detection is done on a per-stream basis. Crucially however, QUIC’s congestion control is still done at the connection level, and not per-stream. This means that even though the streams are conceptually independent, they all still impact QUIC’s singular, per-connection congestion controller, causing slowdowns if there is loss on any of the stream. Put differently: the single HTTP/3+QUIC connection still won’t grow as fast as the 6 HTTP/1.1 connections, similar to how HTTP/2+TCP over one connection wasn’t faster.

Bonus: Is multiplexing important or not?

As described above to some extent and explained in great depth in this presentation, it is typically recommended to send most webpage resources in a sequential rather than multiplexed manner. Put differently, if you have two files, you’re usually better off sending them 11112222 instead of 12121212. This is especially true for resources that need to be completely received before they can be applied, like JS, CSS and fonts.

If that’s the case, we might wonder why we would need multplexing at all? And by extension: HTTP/2 and even HTTP/3, as multiplexing is one of the main features they have that HTTP/1.1 doesn’t. Firstly, some files that can be processed/rendered incrementally do profit from multiplexing. This is for example the case for progressive images. Secondly, as also discussed above, it can be useful if one of the files is much smaller than the others, as it will be downloaded earlier while not delaying the others by too much. Thirdly, multiplexing allows changing the order of responses and interrupting a low priority response for a higher priority one.

A good example that comes up in practice is when using a CDN cache in front of the origin server. Say the browser requests two files from the CDN. The first one (1) is not cached and needs to be fetched from the origin, which will take a while. The second resource (2) however -is- cached at the CDN and thus could be directly transported back to the browser.

Using HTTP/1.1 over one connection, because of HOL blocking, we would have to wait for the origin to fully send (1) before we could start sending (2). This would give us 11112222, but with a long up-front waiting time. Using HTTP/2 however, we can start sending (2) immediately, making use of the “think time” between the CDN and the origin and also “warming up” the connection’s congestion controller. Importantly, if (1) starts arriving before (2) is done, we can now simply start injecting (1)’s data in to the response-stream. This would give us 22111122, with a much shorter waiting time. This can even be used at the very start of the connection using features like Server Push or 103 early hints.

As such, while full “round-robin” multiplexing like 12121212 is rarely what you want for Web performance, multiplexing is definitely a useful feature in general.

Thanks

My thanks goes out to all the people who’ve reviewed this post ahead of time, including: Andy Davies, Dirkjan Ochtman, Paul Reilly, Alexander Yu, Lucas Pardue, Joris Herbots, and neko-suki.

All images were custom made using https://www.diagrams.net. The font used is “Myriad Pro Condensed”.